It would seem strange to me to "review" a book that is now nearly twenty-five years old, and so I won't try. Still,

Illusions of Innocence is a work which demands regular revisiting both as a cogent historical analysis and an insightful critique of American culture. It was in the former capacity that I picked it up recently, planning to reread portions while I waited for a new book to arrive and satisfy my thirst for historical inquiry. Yet, as I flipped through the pages I found myself drawn in by the strong undercurrent of criticism which it offers for America's ongoing self-image. It is, therefore, with regard to how Hughes and Allen's work speaks to contemporary issues that I wish to turn, specifically with what may be said about the recent explosion of interest in the founding fathers.

The authors' purpose in

Illusions of Innocence is simple yet fundamental: to examine how primitivism functioned in American society throughout history. While the focus is on the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, they do not shy away from stepping beyond their stated scope into the twentieth century. Primitivism may be loosely defined as the belief in a sacred, universal primordium which stands outside of time and outside of human influence and to which it is imperative that humanity return. The authors identify two ways in which primitivism has functioned. On the one hand, the primordium can in judgment of the present and act as a guard against any attempts to universalize the particulars of a given culture. In American political thought, this can be typified in Jefferson and the belief that there is a fundamental, natural man who has essential, unalienable rights which transcend time and culture. On the other hand, a group may claim to have definitively captured the primordium, thus identifying their own particular features with universal, sacred truth. Again using American political thought, there is the belief that because America has first and best recognized and enshrined those natural, fundamental rights of man America therefore has the right to impose its representation of those values on other cultures (making the world safe for Democracy). In short, one either believed that the primordium could not be recovered and everyone should therefore be free to approximate it as each saw fit or believed instead that the primordium had been recovered and everyone should be compelled to conform to it.

For early American political theorists--the likes of Jefferson, Adams, and Paine--the primordium which provided the sacred tool for ordering the present was man in his natural state, straight from the hand of the "God of Nature." For the Puritans, the primordium was the covenanted nation of Israel. For most indigenous American religious groups, it was the early church. While Americans often disagreed on precisely what the sacred primitive moment outside of history was, depending on where their allegiances lay, they all agreed that there was such a primordium to be sought after with varying degrees of success. Hughes and Allen cite Sidney E. Mead's

The Lively Experiment to summarize the three characteristic assumptions of American religion: "the idea of a pure and normative beginnings to which return was possible; the idea that the intervening history was largely that of aberrations and corruptions which was better ignored; and the idea of building anew in the American wilderness on the true and ancient foundations."

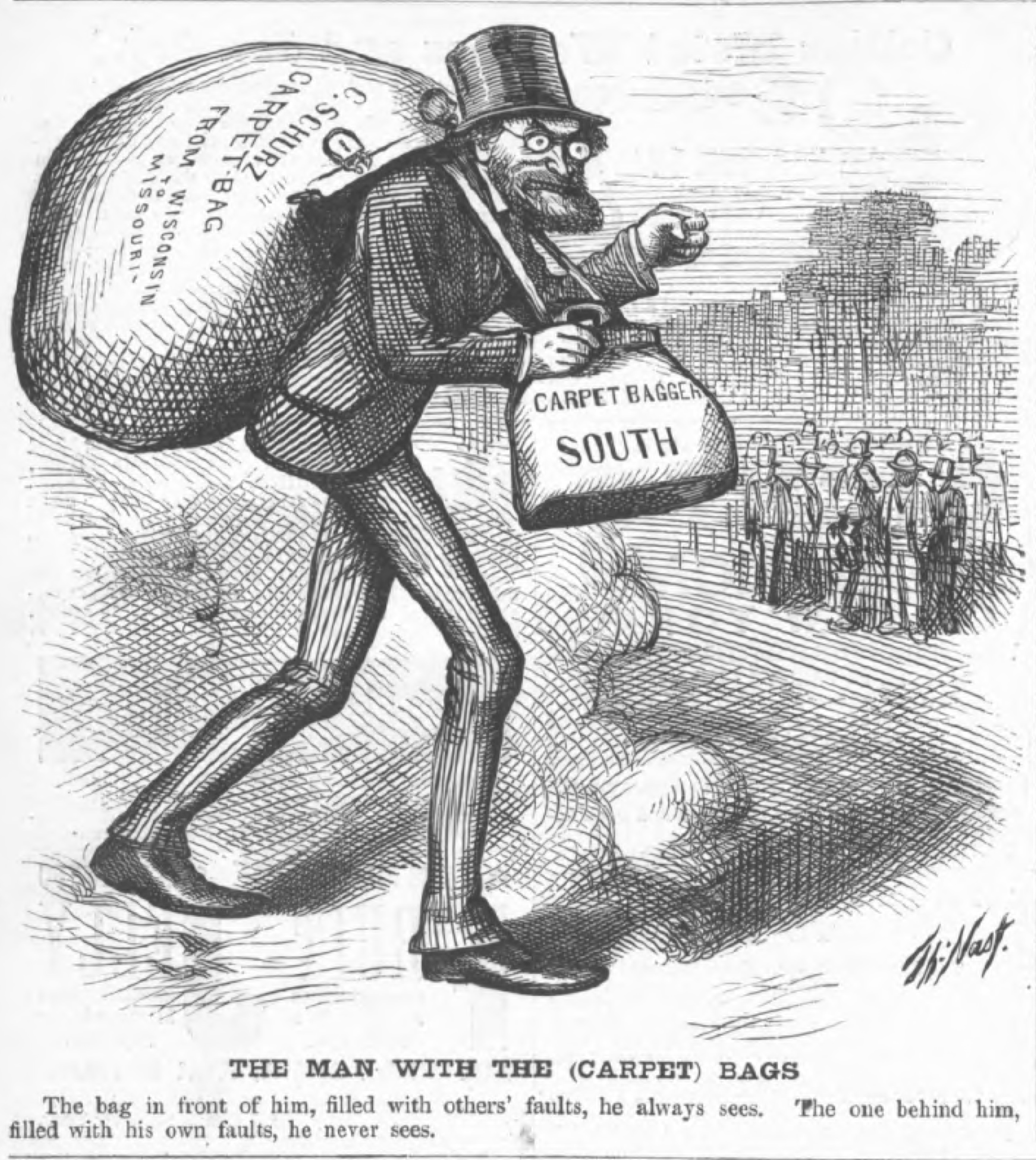

In the recent American political climate, a new (or at least revitalized) primordium has been identified and seized upon by Americans, particularly Republicans. Ron Paul says, "One thing is clear: The Founding Fathers never intended a nation where citizens would pay nearly half of everything they earn to the government." Newt Gingrich muses, "I think Jefferson or George Washington would have rather strongly discouraged you from growing marijuana and their techniques with dealing with it would have been rather more violent than our current government." Michelle Bachmann humorously insists, "Well if you look at one of our Founding Fathers, John Quincy Adams...He tirelessly worked throughout his life to make sure that we did in fact one day eradicate slavery." Appeals to the founding fathers and the Constitution--which, like the Bible, is assumed to be self-interpreting--have exploded onto the political scene as Republicans seek to root and therefore legitimate their beliefs in a mythic, sacred past.

What's more, it is working, and why shouldn't it? Primitivism has always had a tremendous rhetorical effect for Americans because we share in a cultural assumption of exceptionalism, a belief that we stand outside of and in judgment of the profane history and culture of the world. The Puritans founded a fresh and efficient government on primitivist pleas. The Disciples created the fifth largest American denomination of their time in a single generation on the basis of a restoration of the primordium. The South seceded from the Union with primitivism at the heart of its identity. It should be unsurprising then that contemporary politicians should seize on the sacred founders of American civil religion--so eerily analogous to the apostles in the Christian religion--who stand in judgment of our present apostasy. Republicans, thankfully, have seen "the normative beginnings to which return was possible," have identified that "the intervening history was largely that of aberrations and corruptions which was better ignored," and are selling to the public "the idea of building anew...on the true and ancient foundations."

The parallels between the way the founding fathers have been seized upon as a sacred American ideal and the way primitivism has constantly manifest in American religion ought to be immediately striking. This only heighten the irony, then, when Hughes and Allen quote from Carl L. Becker's

Heavenly City, in which Becker offers a criticism of the Enlightenment thinkers whose thought undergirds the Revolutionary experiment. The same criticism which Becker levels against the founders (among others) has an obvious and direct application to those who marshal their memory to their cause today:

...they are deceiving us, these philosopher-historians...But we can easily forgive them for that, since they are, even more effectively deceiving themselves. They do not know that...[what] they are looking for is just their own image, that the principles they are bound to find are the very one they start with. That is the trick they play on the dead.

Of course, Becker is entirely correct. They do deceive themselves more thoroughly than anyone else. This is precisely the reason why the frequent appeals to history on the part of their opponents fall on deaf ears. Just like Disciples and Mormons and Puritans before them, history has no currency in the founding fathers zeal because the founding fathers stand apart from history, as do their modern proponents who have recaptured their values. The ideology which has been discovered in the fathers is an ideology which is immune to the criticism of reason or history;

it is the critic of reason and history. It doesn't matter if in a strictly academic sense John Quincy Adams is not a founding father. Insofar as he is representative of the primordial spirit of the fathers, the invocation of his name is appropriate. It doesn't matter that Jefferson and Washington (and other tobacco lords) probably would not have worked for the violent suppression of marijuana growers in actuality because the ideology they have become synonymous with would be amenable to such action in the present context. Ironically, with the same primordium in mind, Ron Paul can ignore history and context and the changes each have wrought in the way government must operate and make the historically defensible assertion that the founding fathers never conceived of income taxes in their present form.

The purpose here is not to climb up on a high horse to point and laugh at the ignorant Republicans with their primordial myth. It certainly isn't do endorse the Democrats as an alternative. (Like David Lipscomb, I foolishly believe I stand outside of such political partisanship.) In fact, the Democrats have an equal and opposite myth of progress in which they universalize a particular vision of the future rather than of the sacred past to which all reasonable, humane people must attain. While the route is more circumspect, they too--like most Americans--find their way back to grounding this formative myth in a primordium of human rights (intrinsic and apart from the circumstantial trappings of history). Instead, the purpose is to identify, and in doing so hopefully mitigate, the impact of defining myths in our culture. It is to help to reform the appropriate questions, distancing ourselves from the all to easy "Is that really what the founding fathers thought" and getting to the more basic "Should we even care what the founding fathers thought?"

To be sure Hughes and Allen do not want to assert that there are no universals or that they are totally inaccessible, though surely there is no small number of academics today who would agree with one or the other of those premises. Instead, the ongoing purpose of their work and the intent of this reflection on the founding father hysteria is to provide "checks and balances" against too nearly identifying any one person or groups ideology with the universal. Here, perhaps, we have Roger Williams as a model with whom we may critically interact:

For Williams, the radical finitude of human existence, entailing inevitable failures in understanding and action, makes restoration of necessity an open-ended concept. The absolute, universal ideal existed for Williams without question. But the gap between the universal and the particular, between the absolute and the finite, was so great that it precluded any one-on-one identification of the particular with the universal...the best one could do was approximate the universal, an approximation that occurred only through a diligent search for truth.