“We met today for social worship and the elder no being present, the deacon and the brethren would not lead in worship; the sisters went ahead and had singing, prayer and Bible reading. Did we do right? Would it have been right for a sister to have led in the breaking bread?”

In our judgment, you did just right. And if you had added the Lord ’s supper to observances, we should still say you did right. If a company of sisters in a neighborhood in which no brethren lived were to assemble for reading and prayer, what would there be to hinder their observance of the Lord’s supper? And if brethren are present and refuse to lead in the worship, no one can charge that the women usurp authority over them, if they go forward in the performance of duties from which the men shrink. Certainly, such men should never complain because the women outstrip them in zeal and faithfulness.

Showing posts with label gender economics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label gender economics. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

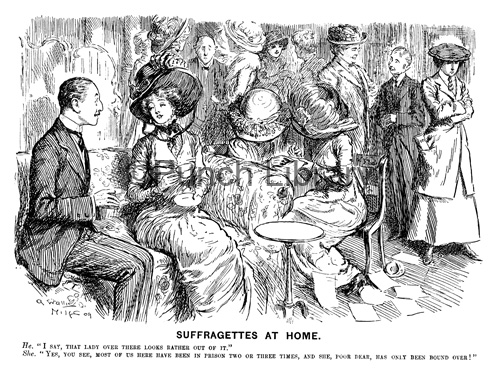

Some Standard Wisdom for the Proactive Church Lady

Having highlighted the seedier side of Stone-Campbell views on the prospects and methods for evangelizing the newly freed slaves, let us turn now to a more egalitarian note. This comes from the Querists' Drawer where Errett and his editorial staff answered questions on belief and practice sent in by readers. Here Errett comes to the defense of some women fed up with their unmotivated fellow congregants.

Saturday, March 16, 2013

A Southern Nation of Speechifiers: Heyrman and Eastman in Conversation

|

| University of Chicago Press |

In Nation of Speechifiers, Eastman argues that far from a great triumph of democratization that once dominated thinking on Jacksonian politics or even the perpetual repression of nonelites that has dominated some feminist and minority histories, the period immediately after the Revolution was one of profound cultural negotiation in which nonelites were able to seize access to public participation in limited but meaningful ways. She looks at politics, education, voluntary associations, trade organizations, publishing, and professional oratory to see the ways that women, children, and racial minorities had a public voice prior to 1810. After that, however, culture shifted as the nation solidified. A war won, a peaceful party transition, and a new vision of suffrage for white men all functioned to close the previously permeable borders of public participation and exclude nonelites.

Yet Eastman glaringly omits religion as an arena in which women, children, and racial minorities had a public voice, a curious oversight particularly in view of Eastman’s stress on oratory as a means of public power. The omission might have made a good avenue for further research had not Heyrman perfectly tackled the question more than a decade earlier. Heyrman takes the same period Eastman considers, treats the same nonelites that Eastman does, but focuses narrowly on religion in the South. The conclusions she draws are largely the same. A newly formed (at least in the South) evangelicalism is initially open to the public voice and at least informal authority of women, children, and racial minorities. After the turn of the century, however, Heyrman exhaustively and convincingly traces the restriction of power into the hands of older white males. She concludes, much as Eastman does, by attacking facile notions of democratization by asking the question democratization for whom.

Eastman’s omission of religion—and of the South and transmontane America almost in their entirety—clearly could have been corrected by reading Heyrman, and the failure to do so borders on inexcusable. Yet readers of Heyrman can benefit from consulting Eastman as well. Heyrman explains the changes in evangelicalism largely as evangelistic necessities. “To put the matter bluntly, evangelicals could not rest content with a religion that was the faith of women, children, and slaves” (193). Growth required appeasing and then appealing to white men, in whose hands all temporal power rested. Eastman suggests there is something more at work in the culture at large here. Eastman’s exclusion of the South from her study may throw this observation into doubt for the arena of Heryman’s work, but nevertheless the question must be raised whether or not evangelistic necessity adequately explains the need for a more male-oriented, “traditional” religious structure. Even if it does, do the broader cultural changes charted by Eastman explain what is driving this evangelistic need? In Heyrman, essentially, evangelicals hit a glass ceiling above which a movement of women could no longer ascend. The early nineteenth century as the period of transition is incidental; it is just when the need for change outweighed the inertia of convention. Eastman’s work suggests there is something more happening in the period.

Both books are supremely readable, and Heyrman in particular has a literary flourish rarely seen among historians. Though my interests and preferences tend toward Heyrman's work, I confidently recommend either for general reading. Eastman's more theoretical framework may scare off non-academics, but anyone who has even a hobbyists interest in the period will be more than amply rewarded by putting in the effort to understand her argument. Together, these two works give a picture of early national American democracy that will challenge the narrative taught in most colleges not to long ago and still, consequently, taught in most grade schools.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Dorothy Day, the Woman

Being myself both anti-abortion and anti-war, both a complementarian and an environmentalist, you might think that I would realize that others, like myself, do not fall neatly into the media constructed left-right continuum of social and political thought. Nevertheless, I still found myself going into The Long Loneliness with the assumption that Dorothy Day, hero of the radical left, must be a rabid feminist of the latest type. Of course, as a historian, I should have realized the anachronism of assuming that a woman who came of age just as so-called first wave feminists were making strides toward legal equality could not be expected to share the concerns of so-called second wave feminists who would begin to blur the distinctions between equality and uniformity in the 1960s. Especially since Day's book was published in 1952. (For all I know, she went on to mirror the changing landscape of feminist thought, but that is a topic for another study.) Whatever my misconceptions and miscalculations, I was pleasantly surprised to read Day's own reflections on her womanhood, not because they necessarily paralleled or reinforced my own thoughts on gender but simply because she represented a strong, thoughtful, articulate woman who was, nonetheless, still a woman and saw herself as distinct from--dare I say complementary to--man.

That observation was inoffensive enough, but she would make others that might not sit quite so well as she pitted her own womanhood against the work she wanted to do:

In that struggle, she did not always choose what the "woman" in her desired. Perhaps, as I think some feminists would argue, this was her overcoming the gender norms foisted upon her by a misogynistic society. Perhaps, as I would suggest, this is merely the sacrifice of self that makes Day's life so profound. Reflecting on her conversion, which precipitated her divorce, she wrote:

It was not all so dreadfully serious, and one anecdote caught my attention precisely for how typically human it was. It reminded of the kind of casual, unreflective assumptions about gender that you hear every day walking through the mall or rattled off in casual conversation around the office. Here she explains to a friend precisely how she sees a mutual acquaintance from her feminine perspective:

And yet, sixty years later, guys like that still exist. Go figure.

I was lonely, deadly lonely. And I was to find out then, as I found out so many times, over and over again, that women especially are social beings, who are not content with just husband and family, but must have a community, a group, an exchange with others. A child is not enough. A husband and children, no matter how busy one may be kept by them, are not enough. Young and old, even in the busiest years of our lives, we women especially are victims of the long loneliness. Men may go away and become desert Fathers, but there were no desert mothers. Even the anchoresses led rather sociable lives, with bookbinding and spiritual counseling, even if they did have to stay in one place.

That observation was inoffensive enough, but she would make others that might not sit quite so well as she pitted her own womanhood against the work she wanted to do:

I am quite ready to concede now that men are the single-minded, the pure of heart, in these movements. Women by their very nature are more materialistic, thinking of the home, the children, and of all things needful to them, especially love. And in their constant searching after it, they go against their own best interests. So, I say, I do not really know myself as I was then. I do not know how sincere I was in my love of the poor and my desire to serve them. I know that I was in favor of works of mercy as we know them, regarding the drives for food and clothing for strikers in the light of justice, and an aid in furthering the revolution. But I was bent on following journalist’s side of the work. I wanted the privileges of the woman and the work of the man, without following the work of the woman. I wanted to go on picket lines, to go to jail, to write, to influence others and so make my mark on the world. How much ambition and how much self-seeking there was in all this!

In that struggle, she did not always choose what the "woman" in her desired. Perhaps, as I think some feminists would argue, this was her overcoming the gender norms foisted upon her by a misogynistic society. Perhaps, as I would suggest, this is merely the sacrifice of self that makes Day's life so profound. Reflecting on her conversion, which precipitated her divorce, she wrote:

I saw the film Grapes of Wrath at this time and the picture of that valiant woman, the vigorous mother, the heart of the home, the loved one, appealed to me strongly. Yet men are terrified of momism and women in turn want a shoulder to lean on. That conflict was in me. A woman does not feel whole without a man. And for a woman who had known the joys of marriage, yes, it was hard. It was years before I awakened without that longing for a face pressed against my breast, an arm about my shoulder. The sense of loss was there. It was a price I had paid.

It was not all so dreadfully serious, and one anecdote caught my attention precisely for how typically human it was. It reminded of the kind of casual, unreflective assumptions about gender that you hear every day walking through the mall or rattled off in casual conversation around the office. Here she explains to a friend precisely how she sees a mutual acquaintance from her feminine perspective:

“I tell you, I do like him. I like him very much. But why do I have to go into raptures about him? Do you want me to fall in love with him? But that is just it—the only thing I do not like about him is that he always is raving about women—kissing his hand to them, going down on his knees to them and saying ‘Ah, how I love them, and how they have wrecked my life!’ Women don’t like such a man. He is too easy to get. They prefer a more aloof type so that if he does make love them they can flatter themselves that there is some rare quality in them which made him succumb.”

And yet, sixty years later, guys like that still exist. Go figure.

Labels:

charity,

children,

divorce,

Dorothy Day,

feminism,

gender economics,

quotes

Thursday, November 29, 2012

The War on Men: A Digest

On Monday, Suzanne Venker published a brief article in which she argues:

I’ve accidentally stumbled upon a subculture of men who’ve told me, in no uncertain terms, that they’re never getting married. When I ask them why, the answer is always the same.

Women aren’t women anymore.

...Fortunately, there is good news: women have the power to turn everything around. All they have to do is surrender to their nature – their femininity – and let men surrender to theirs.

If they do, marriageable men will come out of the woodwork.

Unsurprisingly, the very women who Venker labels as "angry" and "defensive" were outraged by the suggestion and did not hesitate to express that outrage.

Meghan Casserly for Forbes, in one of the tamer articles, writes:

Women, do you hear Suzanne Venker? It’s all your fault. The women’s sexual revolution has left you too aggressive and too needy at the same time—two things “good men” absolutely abhor. But it’s not so much the changing that’s pissing mankind off, ladies. No, we’re pissing them off by expecting them to change along with us. To help us.

Venker writes that women have changed in recent decades and that men have stayed the same–as there hasn’t been a revolution that demanded it. But it seems that very revolution might be upon us. Modern men have two options: to change—or continue going the way of the buffalo.

Erin Gloria Ryan for Jezebel was predictably more outraged:

Venker's piece for Fox News, which extrapolated from changing attitudes about marriage that there's an entire subculture of men who don't want to get married, and that's because women are scaring them away by competing with them, was roundly mocked for being stupid, mindless garbage that paints women as testicle eating castrators and men as delicate babies upset that their feelings aren't being appropriately catered to. Women aren't letting men "win" in this ongoing battle of the sexes, and in response, men are taking their ball(s) and going home. Marital Lysistrata, if you will.

As was her counterpart, Jessica Wakeman, at Frisky:

2. I’ve … stumbled upon a subculture of men who’ve told me, in no uncertain terms, that they’re never getting married. When I ask them why, the answer is always the same. Women aren’t women anymore.

Also, Mommy makes his favorite Hamburger Helper whenever he asks and does not charge any rent for sleeping on that old couch in her basement. And she has no idea all that porn he’s downloaded is the reason why her computer is running so slow.

6. Now the men have nowhere to go.

Waaahhhhh. Fap fap fap fap fap.

Or the similarly lofty response of Kaili Joy Gray for Daily Kos:

Being a lady writer who writes about how ladies totally suck is such hard work.

It's especially hard work if you make your living telling other ladies they shouldn't make a living because of The ChildrenTM and also because it will make men feel bad about themselves. Keeping all the hatred and blame straight can really hurt your ladybrain and make you write things you totally didn't mean to write.

And Kristin Iversen of The L Magazine:

The opening shot [in the War on Men] was sounded today by Suzanne Venker when she posted an article on Foxnews.com entitled "The war on men." [sic] What about the war on capitalization, Suzanne? What about that?

Apparently, capitalization of titles is just one of the casualties in this epic struggle. But no matter, we have more important things to focus on. Namely, why don't men like women anymore? What did women do to fuck up the sweet deal that they've had for centuries? You know. The one where women didn't have the right to vote until less than a hundred years ago. The one where women still don't make anything like equal pay for doing an equal amount of work. The one where women are expected to take on all of the household chores and childcare responsibilities and look the other way while men have as much freedom as they want. THAT SWEET DEAL.

Emma Gray for the Huffington Post quips:

Meanwhile, we women will quit our jobs, purchase aprons with our last paychecks and bake like it's 1955. A workforce reduced by nearly half? That's bound to get this society headed in the right direction.

Meagan Morris for Cosmopolitan chimes in:

We've come a long way as a gender since the birth of feminism and—gender pay gap, be damned—have the same rights and opportunities as our dude counterparts.

Oopsies, though: We silly women now have too much equality, according to Suzanne Venker. The Fox News columnist hypothesizes that the reason why so-called "marriageable men" don't want to get married is because today's women don't make them feel like the super manly men women of say, the 1800s, would have...

So, all of us single ladies are destined to be single forever—and its our own fault—because we want to have careers and fulfilling lives.

Then there was Hanna Rosin at Slate:

I knew that women had become more educated. I knew they were steadily earning more money. I knew they had gained a lot of power of late, and sometimes even more money and power than the men around them. But I did not realize they had become so powerful that they could mess with the men’s DNA. How did I miss that? How has J.J. Abrams not made a movie about it?

Unfortunately, Venker is somewhat enigmatic about how to reverse this problem, beyond a few vague clues. Women, she says, “have the power to turn everything around” (Duh, of course, we have ALL the power). “All they have to do is surrender to their nature – their femininity – and let men surrender to theirs.” Surrender to my femininity. Surrender to my femininity. I get the general idea but what does it mean, like, in practice? Not wear pants so much? Let my hair grow. Ask my boss to pay me a little less? Open to ideas.

Are you noticing a trend here? No, it isn't the generally liberal or openly feminist bent of these publications. It isn't the condescending attitude that suggests that any challenge to prevailing notions about gender in public discourse is beneath serious reply. It isn't even the logically fallacious, but nevertheless ubiquitous, guilt-by-association with Phyllis Schlafly (which I did my best to edit out). It's the fact that all of these commentators are women.

Granted, I didn't lift up there skirts and check (as if any of them wear skirts...ha), though that surely would have been my prerogative in 1955 or the 1800s or whenever we're locating that fictionalized era when women were actively, systematically, and universally oppressed by men. Nevertheless, it seems clear that what we have here is a bunch of women sitting around in a closed off group trying to decide whether or not and how men are trying to oppress women and failing as men. Go figure.

Speaking on behalf of the testicled among us, or at least as one male among many, you women are welcome to continue to ascend in the workforce. Most of my colleagues are already women, as are most of my immediate supervisors. Continue to dominate academics. Be ever more consciously aggressive, more coldly rational, more unreservedly sexual, more delightfully vulgar because, after all, men have gotten away with it for years and anything we can do, you can do better. Earn equal pay for equal work, and, for the sake of reparations, reverse the pay gap for a while just to teach us a lesson. You have my permission, which you neither need nor want and which is undoubtedly a mere vestige of a paternalistic cultural heritage passed unconsciously to me by my forefathers (<--term deliberately not gender inclusive). Meanwhile, all I ask for is the simple right to find those qualities unattractive. If the idea of my home becoming a staging ground for working out gender equality doesn't comport with the notions of domestic bliss that I developed when I was a little boy playing house and you were a little girl playing sister suffragette, I trust you won't think me too primitive. While you are off pursuing your dreams, I ask only that you don't count among your goals the wholesale destruction of my dream of enjoying a wife who makes me feel like a man, the sort of man Nick Charles was in the 1930s with his young, rich, opinionated, strong-willed wife who adored him. I have never, nor would I ever, force a woman to do anything, but you'll forgive me if I don't buy into the newest, shiniest model of woman just because you're telling me she's the wave of the future. The old model works just fine, the kind who recognizes that the quests for love and equity are sometimes adversarial.

So you can scoff if you want and hurl petty insults at Suzanne Venker, but--personally, anecdotally--there seems to be more than a little truth in the argument that men aren't interested in competing all day at work and coming home to find domestic competition hovering just beneath the surface. What do you care? You don't want men like me anyway, and the men you do want don't want women like Suzanne Venker or Phyllis Schafly anyway--you know, the publicly outspoken, well-educated, career women that feminists are trying to get rid of.

If we're lucky, men will go on blaming the demise of marital tranquility on women; women will persistently nag men to change with the times and lament the failures of the brutish sex when empowered women can't find husbands; and before it's all over, maybe the world won't collapse under the wait of its own mushrooming population.

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Anarchism and the Just Society

The following is part of the Anarchy in May series which examines Christian anarchism and quotes prominent Christian anarchist thinkers. For a more detailed introduction and a table of contents, please see Anarchy in May: Brief Introduction and Contents.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

There is a great deal to commend Vernard Eller’s arguments about human attempts to construct a classless society, but an arguments merits are normally apparent on its face. To that extent, I intend to let Eller’s point speak for itself. No argument, however, is entirely invulnerable to criticism. Two such criticisms came to my mind while I was reviewing Eller’s case that bear engagement. Though I do not think either is ultimately justified, the fact that Eller does not address them specifically compels me to address them.

The first and most obvious criticism that might arise from those who advocate revolutionary attempts to establish equity is that Eller’s Christian alternative does not actually achieve the ends for society that they pursue. No matter how hard we try, simply ignoring social inequality does not resolve the reality of it. As long as the “oppressing classes” continue to have recourse to their means of oppression, the “oppressed classes” will continue to be oppressed.

This is undoubtedly true. It must be remembered, however, that Christian anarchism makes no pretense of trying to reform human society through human effort. In fact, it is predicated precisely on rejecting such a pretension. Eller makes the point quite clearly that all human means for establishing social equity necessarily involve the use of force (in some fashion) which is itself a form of social oppression, even if it is the “oppressed” who are oppressing the “oppressors.” Christian anarchism doesn’t provide an alternative human means for achieving human ends, but a rejection of human means and human ends in favor of divine ones.

The church, in this understanding, becomes the only truly classless, and therefore just, society because it adopts, insofar as it is possible, the divine perspective of unity in Christ. When Paul says that there is no Greek or Jew, male or female, he does not believe that humanity becomes uniform by entrance into the church. Instead, the church becomes the proleptic experience of the kingdom on earth in which the incidentals which assume the status of identity in human society are relegated to their proper sphere.

This provides a perfect segue into the second objection: if classification as a means of domination is eliminated in the Christian community, what is to be made of the various economic recognitions of features such as gender in the church. If anarchism and its attempts to construct an equitable society by divine means is in fact the true means for achieving justice, does it not necessarily follow that people in the church cease to recognize as significant distinctions in gender?

I suspect that for Eller this is not so much an objection as a recognition of his logical conclusion. He appears to be the egalitarian type of anarchist more in the tradition of Garrison than Lipscomb. Being myself nearer to the latter, however, it is important to stress that egalitarian gender economics are only one possible implication to be drawn from Eller’s argument.

Even Eller recognizes that matters of sex, race, or socio-economic status are significant insofar as they are necessary categories by which humanity interacts with the world. For Eller this is an unfortunate byproduct of human finitude. He does not seem to recognize that there are realities which correspond to the categories which are generally labeled “oppressive.” The essence of anarchism does not need to be the elimination of all distinction because distinction is not only relevant and representative of reality but it is arguably the preeminent reality, enshrined before time in the trinitarian God and established as the predicate reality for a creation which is genuinely ex nihilo. (Eller presses this issue to its breaking point, wanting to blur even the distinctions between species as he makes a point to refer to sparrows as “individuals” in the same way that people are “individuals.”)

Instead, what Jesus does and what the anarchist vision of the church does is to divorce classification from value. This is the core of the complementarian argument of ontological equality and economic difference. It is critical to realize that difference in race, socio-economic status, and gender are non-essential, which is to say that they are not of the essence of things not that they are not meaningful. With this understanding in view, Eller’s stress on the church as the congregation of individuals standing equally before God and equally in one another’s estimation can be fully embraced.

Whatever you are, you are first and foremost a child of God, a sibling in Christ, and an expectant participant in the Kingdom of Heaven. That is what identifies us as Christians. That we may function differently in the church on the basis of the incidentals of our existence does not undermine that truth or in any way diminish its supreme importance. (And that stands not just for the issue of gender economics but also for the way people of different socio-economic status function differently but equally in the mission of the church not to mention countless other less controversial economic distinctions).

Undoubtedly, the fact that I agree with so many of Eller’s premises means that I am omitting or overlooking other potential errors in his thinking (any of which I would be happy to have pointed out to me). Nevertheless, it seems hard to contradict Eller’s acute sense of the flaw in historical and ongoing attempts by humanity to imagine and pursue and truly equitable society. The just society will always be out of the reach of optimistic human hands because humanity lacks truly just mechanisms of actualizing its vision, even if that vision were truly just.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

There is a great deal to commend Vernard Eller’s arguments about human attempts to construct a classless society, but an arguments merits are normally apparent on its face. To that extent, I intend to let Eller’s point speak for itself. No argument, however, is entirely invulnerable to criticism. Two such criticisms came to my mind while I was reviewing Eller’s case that bear engagement. Though I do not think either is ultimately justified, the fact that Eller does not address them specifically compels me to address them.

The first and most obvious criticism that might arise from those who advocate revolutionary attempts to establish equity is that Eller’s Christian alternative does not actually achieve the ends for society that they pursue. No matter how hard we try, simply ignoring social inequality does not resolve the reality of it. As long as the “oppressing classes” continue to have recourse to their means of oppression, the “oppressed classes” will continue to be oppressed.

This is undoubtedly true. It must be remembered, however, that Christian anarchism makes no pretense of trying to reform human society through human effort. In fact, it is predicated precisely on rejecting such a pretension. Eller makes the point quite clearly that all human means for establishing social equity necessarily involve the use of force (in some fashion) which is itself a form of social oppression, even if it is the “oppressed” who are oppressing the “oppressors.” Christian anarchism doesn’t provide an alternative human means for achieving human ends, but a rejection of human means and human ends in favor of divine ones.

The church, in this understanding, becomes the only truly classless, and therefore just, society because it adopts, insofar as it is possible, the divine perspective of unity in Christ. When Paul says that there is no Greek or Jew, male or female, he does not believe that humanity becomes uniform by entrance into the church. Instead, the church becomes the proleptic experience of the kingdom on earth in which the incidentals which assume the status of identity in human society are relegated to their proper sphere.

This provides a perfect segue into the second objection: if classification as a means of domination is eliminated in the Christian community, what is to be made of the various economic recognitions of features such as gender in the church. If anarchism and its attempts to construct an equitable society by divine means is in fact the true means for achieving justice, does it not necessarily follow that people in the church cease to recognize as significant distinctions in gender?

I suspect that for Eller this is not so much an objection as a recognition of his logical conclusion. He appears to be the egalitarian type of anarchist more in the tradition of Garrison than Lipscomb. Being myself nearer to the latter, however, it is important to stress that egalitarian gender economics are only one possible implication to be drawn from Eller’s argument.

Even Eller recognizes that matters of sex, race, or socio-economic status are significant insofar as they are necessary categories by which humanity interacts with the world. For Eller this is an unfortunate byproduct of human finitude. He does not seem to recognize that there are realities which correspond to the categories which are generally labeled “oppressive.” The essence of anarchism does not need to be the elimination of all distinction because distinction is not only relevant and representative of reality but it is arguably the preeminent reality, enshrined before time in the trinitarian God and established as the predicate reality for a creation which is genuinely ex nihilo. (Eller presses this issue to its breaking point, wanting to blur even the distinctions between species as he makes a point to refer to sparrows as “individuals” in the same way that people are “individuals.”)

Instead, what Jesus does and what the anarchist vision of the church does is to divorce classification from value. This is the core of the complementarian argument of ontological equality and economic difference. It is critical to realize that difference in race, socio-economic status, and gender are non-essential, which is to say that they are not of the essence of things not that they are not meaningful. With this understanding in view, Eller’s stress on the church as the congregation of individuals standing equally before God and equally in one another’s estimation can be fully embraced.

Whatever you are, you are first and foremost a child of God, a sibling in Christ, and an expectant participant in the Kingdom of Heaven. That is what identifies us as Christians. That we may function differently in the church on the basis of the incidentals of our existence does not undermine that truth or in any way diminish its supreme importance. (And that stands not just for the issue of gender economics but also for the way people of different socio-economic status function differently but equally in the mission of the church not to mention countless other less controversial economic distinctions).

Undoubtedly, the fact that I agree with so many of Eller’s premises means that I am omitting or overlooking other potential errors in his thinking (any of which I would be happy to have pointed out to me). Nevertheless, it seems hard to contradict Eller’s acute sense of the flaw in historical and ongoing attempts by humanity to imagine and pursue and truly equitable society. The just society will always be out of the reach of optimistic human hands because humanity lacks truly just mechanisms of actualizing its vision, even if that vision were truly just.

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Anarchy in May: Eller on the Just Society (Pt. 2)

The following is part of the Anarchy in May series which examines Christian anarchism and quotes prominent Christian anarchist thinkers. For a more detailed introduction and a table of contents, please see Anarchy in May: Brief Introduction and Contents.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Marxism is the easiest and most obvious choice for demonstrating the folly of human attempts to construct a classless society, but Eller is quick to recognize that the projects of social equity are not limited to efforts by workers to control the means of production or even by groups attempting to overthrow nation-states to acheive liberation. There are oppressed classes (real or imagined) constantly struggling to level the social playing field that have nothing to do, overtly, with political communism. According to Eller, these movements in favor of "classlessness" suffer from the same methodological flaws that Marxism does.

As an example, Eller offers an analysis of feminism:

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Marxism is the easiest and most obvious choice for demonstrating the folly of human attempts to construct a classless society, but Eller is quick to recognize that the projects of social equity are not limited to efforts by workers to control the means of production or even by groups attempting to overthrow nation-states to acheive liberation. There are oppressed classes (real or imagined) constantly struggling to level the social playing field that have nothing to do, overtly, with political communism. According to Eller, these movements in favor of "classlessness" suffer from the same methodological flaws that Marxism does.

As an example, Eller offers an analysis of feminism:

The clear and laudable goal of the feminist movement is to create a society in which the social distinctions between male and female are reduced to adiaphora, matters of no consequence. Not only any hint of inequality but even the distinguishing marks of the two are to be minimized. A true classlessness is to transpire. Yet that classlessness cannot happen by the direct approach of playing down the distinctions; the power of the oppressing class must first be broken. No, the immediate steps must point directly away from the ultimate goal they would serve.

Thus: “Yes, the two genders should be treated without distinction.” So, from time immemorial we have had us an English language that enables us to speak by the house without dropping so much as a hint that two different genders of human beings are involved, that there even exists a distinction known as “gender.” Yet, that way hardly serves the raising of feminine class consciousness. Therefore, the rule now is to speak (with doubled pronouns and the like) so that the gender distinction is always prominent, to use gendered terminology in preference to the ungendered, to take care in specifying women at least as often as men. The feminist grammar is designed to serve gender awareness, not the classlessness of gender ignorance.

Thus: “Yes, the goal is that gender distinctions disappear.” However, on the way to that goal, feminine class distinction is necessary—to the point that one theology cannot be taken as serving human beings indiscriminately. There must now be a feminist theology in which women can have their special concept of God, their definition of salvation, their preferred reading of the gospel. Yes, just that far must the commonality of women and men be denied—for the sake of ultimate classlessness!

Thus: “Yes, we look for the day when the distinction between women and men will be seen as insignificant if not nonexistent.” Nevertheless, for the sake of the ideological solidarity necessary to get us there, we find it right to posit an absolute moral distinction between the sexes—namely, that it is men who cause wars and that, if given the chance, women would create peace.

…In undoubted sincerity, the feminists claim that their interest is not simply in liberating themselves but in liberating men as well. Yet what must be recognized is that this has been the standard revolutionary line of every class war ever mounted. However, the question is whether true classlessness ever can be achieved through one class’s gaining the power to dictate the terms of that classlessness. Even more, can it be called “liberation” for other people to take it upon themselves to liberate you according to their idea of what your liberation should be? It strikes me that “liberation” is one term the person will have to define for himself.

But if “class distinction” and “class struggle” be our chosen means, is it possible that the contradiction ever can be overcome?—that “classlessness” can ever mean anything other than “we are now all of one class, because ours is it”’ or “liberation” mean anything other than “you are no liberated, because we are in a position to tell you that you are”?

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Complementarianism: Olson's Gordian Knot

The following is part of an ongoing response to Roger E. Olson’s critique of extreme complementarianism. For the origin and nature of these posts, see Complementarianism: A Defense from a Nobody.

________________________________________________________________________

Let us shift now from complementarianism in theory and Olson's critique of it to a subsequent post where Olson attempts to upend complementarianism. He proposes to offer "a true conundrum that exposes the impossibility of consistent complementarianism" and solicits in response possible solutions from "leading evangelical complementarian theorists." Unfortunately, I am not a leading theorist in any respect, and thus my opinion has only marginal weight for Olson--as I am forced to conclude does the opinions of the millions of regular complementarians who go around every day not treating their wives like children or living in abject, debilitating subjugation to their husbands. Nevertheless, I will present Olson's Gordian Knot and, with my meager skills, attempt to untie it from the complementarian position I have outlined previously.

The scenario Olson describes is difficult, admittedly, but perhaps not in the way he thinks. It isn't difficult to resolve logically; its difficulty lies in the existential turmoil it evokes. The force of his argument rests primarily in its appeal to the universal human inclination to be covetous of what we own. Anyone who has been married for any period of time has weathered some kind of financial difficulty and, in all likelihood, has butted heads with his or her spouse over the proper course to take. When you pair that shared experience with the ubiquitous presence in sinful humanity of a desire to possess and preserve "treasures on earth," it is understandable why Olson's straw complementarians have shied away from answering.

The resolution, such as it is, comes first through reorienting the ethical priorities. For Olson, the clear focus is on the ethics of financial stewardship (to use a gross euphemism). When presented with the potential objection that the limit of submission is sin, he counters that "[the complementarian] has to define “sin” in such a way as to exclude from it the wife’s knowing participation in financial ruin for their whole family." What looms large in the ethical picture then is the suggestion that the possibility of financial ruin is more critical than the possibility that some tertiary Christian principle (something totally incidental like submission) might be violated.

Instead of focusing on the dire prospect that "money for their childrens’ college educations and for retirement" might not be there--concerns which smack of an affluent Christianity foreign to the apostolic age, or to most Christian ages for that matter--the primary ethical question ought to be whether or not the foundational Christian principle of self-sacrificial love is at play. With this being the new focus, there are a number of actions which would be morally virtuous regardless of the consequences (and thus undermining Olson's utilitarian vision of ethics). For example, it would be morally virtuous for the wife to opt to submit to the husband and allow the money to be invested. If the money should be lost, credit God with using the wife's sacrifice as a tool for teaching the husband humility. If the investment should prove profitable, credit God with using the husband's prudence as a tool for teaching the wife humility. In either case, whatever happens to the money is incidental. The wife's choice to submit is morally virtuous.

Before any objections to this are raised, let me continue by adding that it would also be morally virtuous if the husband opted to forgo the investment out of sacrificial love for his wife. It is a fool (or a polemicist) who believes that true leadership consists of always getting your way. Plato understood leadership to be whatever actions best ensured that all those led were maximizing their potential. Paul had a less calculating but nonetheless compatible vision when he told husbands that they should give themselves up for their wives as Christ gave himself up for the church. If the investment turns out to have been unsound for others, credit God with using the wife's prudence as a tool for teaching the husband humility. If the investment turns out to have been sound for others, credit God with using the husband's sacrifice as a tool for teaching the wife humility. In either case, the husband can only ever act virtuous when he sacrifices his will out of love for his wife.

The ultimate issue at stake here is not how to make sound investments but how to have a sound marriage before God. The key to this does not lie in equal rights or even in a calculated, non-traditional division of labor. It lies in the willingness of the spouses to emulate Jesus Christ, who submits himself eternally to God the Father and who gave himself up ultimately for his bride the church. As the hypothetical couples counselor, I don't care at all what happens to their money. I'm not their stockbroker. My concern is helping them to grow into conformity with the image of Christ, for which submission is essential. Olson frames the question as a conflict between doing what is good and doing what is legal, but in reality it is a clash between doing what is right and doing what is desirable. The focus on the money betrays who our true master is. If it is God rather than Mammon, then the issue comes into sharper focus.

Not, I imagine, for Olson, mind you. It is clear from his proposed dilemma that he sees unsound investment as a sin (a damning judgment on so many in America and the world right now). There is a more unsettling undercurrent to Olson's argument, however, a response to which may sum up my point here. In his opening salvo, Olson poses this question with apparent indignation: "What is permanent, docile, subordination and submission if not a curse?" I would suggest that it is the appropriate human disposition before God. If submission is a curse, than the Son is accursed of the Father. If submission is a curse, then Adam and all of creation were cursed before Even ever arrived on the scene. If submission is a curse, then Paul enjoins all Christians to be cursed by one another and by God. In fact, the permanent, docile, and voluntary (an adjective that Olson always seems to omit) submission before God is the wonderful disposition in which God exalts and beatifies all creation. That wives may be asked to practice this before their husbands ("as to the Lord"), Christians before one another, congregants before elders, children before parents, slaves before masters, and on and on is not the shame of anyone but to their glorious and eternal benefit.

________________________________________________________________________

Let us shift now from complementarianism in theory and Olson's critique of it to a subsequent post where Olson attempts to upend complementarianism. He proposes to offer "a true conundrum that exposes the impossibility of consistent complementarianism" and solicits in response possible solutions from "leading evangelical complementarian theorists." Unfortunately, I am not a leading theorist in any respect, and thus my opinion has only marginal weight for Olson--as I am forced to conclude does the opinions of the millions of regular complementarians who go around every day not treating their wives like children or living in abject, debilitating subjugation to their husbands. Nevertheless, I will present Olson's Gordian Knot and, with my meager skills, attempt to untie it from the complementarian position I have outlined previously.

Suppose a married couple comes to you (the complementarian pastor or counselor or whatever) for advice. They are both committed evangelical Christians who sincerely want to “do the right thing.” They are trying to live according to the guidelines of evangelical complementarianism. However, a problem has arisen in their marriage. The wife acquired sound knowledge and understanding of finances including investments before the couple became Christians. The husband is a car mechanic who knows little to nothing about finances or investments. A good, trusted friend has come to the husband and offered him an opportunity to make a lot of money by investing the couple’s savings (money for their childrens’ college educations and for retirement) in a capital venture. The husband wants to do it. The wife, whose knowledge of finances and investments is well known and acknowledged by everyone, is adamantly opposed to it and says she knows, without doubt, that the money will be lost in that particular investment. She sees something in it the husband doesn’t see and she can’t convince him that it is a bad investment. The husband wants to take all their savings and put it into this investment, but he can’t do it without his wife’s signature. The wife won’t sign. However, after long debate, the couple has agreed to leave the matter in your hands. The husband insists this is a test of the wife’s God-ordained subordination to him. The wife insists this is an exception to their otherwise complementarian marriage. You, the complementarian adviser of the couple, realize the wife is right about the investment. The money will be lost if the investment is made. You try to talk the husband out of it but he won’t listen. All he’s there for is to have you decide biblically and theologically what she, the wife, should do. What do you advise?

The scenario Olson describes is difficult, admittedly, but perhaps not in the way he thinks. It isn't difficult to resolve logically; its difficulty lies in the existential turmoil it evokes. The force of his argument rests primarily in its appeal to the universal human inclination to be covetous of what we own. Anyone who has been married for any period of time has weathered some kind of financial difficulty and, in all likelihood, has butted heads with his or her spouse over the proper course to take. When you pair that shared experience with the ubiquitous presence in sinful humanity of a desire to possess and preserve "treasures on earth," it is understandable why Olson's straw complementarians have shied away from answering.

The resolution, such as it is, comes first through reorienting the ethical priorities. For Olson, the clear focus is on the ethics of financial stewardship (to use a gross euphemism). When presented with the potential objection that the limit of submission is sin, he counters that "[the complementarian] has to define “sin” in such a way as to exclude from it the wife’s knowing participation in financial ruin for their whole family." What looms large in the ethical picture then is the suggestion that the possibility of financial ruin is more critical than the possibility that some tertiary Christian principle (something totally incidental like submission) might be violated.

Instead of focusing on the dire prospect that "money for their childrens’ college educations and for retirement" might not be there--concerns which smack of an affluent Christianity foreign to the apostolic age, or to most Christian ages for that matter--the primary ethical question ought to be whether or not the foundational Christian principle of self-sacrificial love is at play. With this being the new focus, there are a number of actions which would be morally virtuous regardless of the consequences (and thus undermining Olson's utilitarian vision of ethics). For example, it would be morally virtuous for the wife to opt to submit to the husband and allow the money to be invested. If the money should be lost, credit God with using the wife's sacrifice as a tool for teaching the husband humility. If the investment should prove profitable, credit God with using the husband's prudence as a tool for teaching the wife humility. In either case, whatever happens to the money is incidental. The wife's choice to submit is morally virtuous.

Before any objections to this are raised, let me continue by adding that it would also be morally virtuous if the husband opted to forgo the investment out of sacrificial love for his wife. It is a fool (or a polemicist) who believes that true leadership consists of always getting your way. Plato understood leadership to be whatever actions best ensured that all those led were maximizing their potential. Paul had a less calculating but nonetheless compatible vision when he told husbands that they should give themselves up for their wives as Christ gave himself up for the church. If the investment turns out to have been unsound for others, credit God with using the wife's prudence as a tool for teaching the husband humility. If the investment turns out to have been sound for others, credit God with using the husband's sacrifice as a tool for teaching the wife humility. In either case, the husband can only ever act virtuous when he sacrifices his will out of love for his wife.

The ultimate issue at stake here is not how to make sound investments but how to have a sound marriage before God. The key to this does not lie in equal rights or even in a calculated, non-traditional division of labor. It lies in the willingness of the spouses to emulate Jesus Christ, who submits himself eternally to God the Father and who gave himself up ultimately for his bride the church. As the hypothetical couples counselor, I don't care at all what happens to their money. I'm not their stockbroker. My concern is helping them to grow into conformity with the image of Christ, for which submission is essential. Olson frames the question as a conflict between doing what is good and doing what is legal, but in reality it is a clash between doing what is right and doing what is desirable. The focus on the money betrays who our true master is. If it is God rather than Mammon, then the issue comes into sharper focus.

Not, I imagine, for Olson, mind you. It is clear from his proposed dilemma that he sees unsound investment as a sin (a damning judgment on so many in America and the world right now). There is a more unsettling undercurrent to Olson's argument, however, a response to which may sum up my point here. In his opening salvo, Olson poses this question with apparent indignation: "What is permanent, docile, subordination and submission if not a curse?" I would suggest that it is the appropriate human disposition before God. If submission is a curse, than the Son is accursed of the Father. If submission is a curse, then Adam and all of creation were cursed before Even ever arrived on the scene. If submission is a curse, then Paul enjoins all Christians to be cursed by one another and by God. In fact, the permanent, docile, and voluntary (an adjective that Olson always seems to omit) submission before God is the wonderful disposition in which God exalts and beatifies all creation. That wives may be asked to practice this before their husbands ("as to the Lord"), Christians before one another, congregants before elders, children before parents, slaves before masters, and on and on is not the shame of anyone but to their glorious and eternal benefit.

Labels:

complementariansim,

gender economics,

marriage,

money,

obedience,

Roger E. Olson,

submission

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

Complementarianism: Will To Power

The following is part of an ongoing response to Roger E. Olson’s critique of extreme complementarianism. For the origin and nature of these posts, see Complementarianism: A Defense from a Nobody.

________________________________________________________________________

I suppose there is very little to offend in my previous thoughts about the theoretical value of understanding men and women as different but equal. After all, even Dr. Olson admits that to one degree or another this is a universally recognized truth. What was controversial, and will be addressed at greater length here, is the suggestion that those difference cannot be neatly compartmentalized into the incidences of anatomy. There are, to put it crudely, substantial economic distinctions between males and females that cannot be reduced into prescriptions about whether God intended semen to come out of your or go into you. It is a tragic inevitability that more time should need to be spent on this latter fact than on the former, since the truth that God is a God who delights in constructive difference ought to be (and in my experience is) the focal point of complementarian thought. I regret that by focusing on the secondary, pragmatic aspects of complementarianism I legitimize, in a sense, Olson's complaint that for complementarians the "emphasis is not on males and females complementing each other but on females being submissive to males." Yet it should be recognized that this criticism is self-propagating. After all, if egalitarians and complementarians disagreed about value and function rather than on women in the pulpit then the conversation would be dominated by the former issue and the latter would be ignored. It is out of polemical necessity more than anything else that the debate has been translated from the core issues into mere accidents. Insofar as complementarians through repetitive arguments and microscopic focus on application forget to stress the essential truths of what is a more comprehensive anthropology, that shortcoming is ours as humans not a flaw in the truths which we feel compelled to express.

With that said, the other shoe is ready to drop. I believe that wives should submit to their husbands and that women should not exercise authority over men in the congregation. These do not encapsulate my complementarian beliefs, but they are nevertheless an undeniable product of them. From here, there are countless directions I could go. I might attempt to counter Olson's assertion that only unabashed and "never really consistently" literalism can produce complementarian readings of Scripture by pointing out how theologically dangerous it is to excise under the guise of "cultural particularity" commands which are rooted in creation and yoked with soteriology. I could talk about the countless other social norms which Jesus and Paul were willing (even eager) to transgress and contrast it with their marked reluctance to do so with certain features of gender economics. I could trace the full and rich biblical picture of complementarian gender relations as they are depicted as fruitful and righteous throughout Scripture, demonstrating a marked consistency between Old and New Covenant gender economics. But I won't, in large part because my point here is not to prove complementarianism. It is to demonstrate that there can be and are complementarians whose interests lie beyond (and even exclude) the end of subjugating women, to correct Olson's egregious characterization that in complementarianism "adult women have pretty much the same role as children vis-à-vis adult men."

Ultimately, I think the concern most egalitarians express (by which, I of course mean the revulsion most egalitarians feel) regarding complementarianism is born out of a capitulation to modern ideas of rights, authority, and power. In essence, there is a suggestion that unless women are given authority, they are somehow devalued. Unless they are presented with a full compliment of rights, they are second-class citizens. Unless they have power, they are helpless and destined for abuse (a specter Olson proves all to eager to conjure). In short, it is hard not to be left with the impression that, whether consciously or unconsciously, many egalitarians have bought into the anthropology of a post-nietzschean West which glorifies the will to power. If women are fully human they must have the opportunity to pursue their ambition to seize the highest clerical offices, command the most powerful pulpits, vie for control in their marriages, and to become the Übermensch (rather than, as in Nietzsche, simply to birth the Übermensch).

Egalitarians, I imagine, would balk at that depiction of their beliefs and particularly its marriage to so dark a figure as Nietzsche. (Though, for my part, I find it less offensive a picture than that of complementarians as domineering patriarchs seeking eagerly to have paternal authority over all 3.5 billion women in the world.) Certainly, I am open to the idea that the above has at least as much rhetorical flourish as it does substance. Egalitarians would surely not debate, however, that there motivating impulse is equal rights, rich as that term is with savory left-wing utopian connotations. The problem arises, however, in that I don't believe in rights. I don't believe we have them, and I certainly don't think it is expressive of the Christian ethos to pursue them for ourselves. The quest for power, authority, and rights--which I will from here on collapse into the concept of authority, since it is primarily the right to have authority and the power derived from it on which the debate centers--is found nowhere in the Gospel. Instead, all authority is derived from God and given, qualified as it is, as a gift from Him. It is not a right to be seized but a commission to be accepted.

Instead, the Gospel is a narrative of submission and self-sacrifice. Jesus Christ, to whom all authority had been given, is the prime example of this. Consider the way he exercised his authority throughout his ministry. It was not in dictatorial commands to his disciples (male or female). It was not in domination over them. Instead, he assumed the role of a servant: feeding the hungry, encouraging the downtrodden, forgiving the sinner, and washing the feet of his disciples. The same ethos will carry into the earliest church. Though we occasionally see Paul making appeals to his authority (acknowledging always its derivative nature), the overwhelming example given by the apostles is one of unqualified service and the exhortation for Christians to do the same. Christ foreshadows and Paul recalls the cross as the central image of power, ironically redefined by the Gospel, for the whole Christian system. It is in dying the Christ ultimately defeats death and in our participation in that self-sacrificial act that Christians ultimately free themselves from it. Christian virtue is defined by and emulates this core self-sacrificial act. It does not strive after positions of power; it deliberately eschews them, allowing Christ to become a new kind of king. If our understanding of authority--its scope and function--were genuinely cruciform, then the Bible could place women in a perpetual and inviolable state of servitude and, far from making their position lamentable, it would glorify them in so doing.

Of course, it doesn't and no self-respecting complementarian thinks that it does. The biblical picture of gender economics is one of mutual self-sacrifice and voluntary submission, because the virtues embodied in the cross are by no means exclusive to one sex. The most complete and wonderful picture is in the much maligned household codes in Ephesians, which gives two interrelated commands: wives submit to your husbands (as the church submits to Christ) and husbands sacrifice yourself for your wife (as Christ sacrificed himself for the church). It is important first to note that all submission and self-sacrifice is related directly back to Christ as the exemplar. It is not the Christ came and made himself a servant because he was less than those he came to serve. He humbled himself in spite of his superiority. Moreover, Christ did not sacrifice himself as it suited him and to the degree it suited him but completely and in ways which most profoundly effected him. What is depicted in the relationship between Christ and the church is not the degree of authority which is being conferred upon husbands but the nature of the relationship. What is being prescribed for wives and husbands is, in its essence, a common disposition toward one another. After all, Christians are exhorted to submission (the same kind of submission that wives are specifically enjoined to choose) to all other Christians in the verse immediately prior. The image is of a husband who empties himself in the act of sacrifice for his wife so that there is nothing in him that self-centered. He acts purely in love for his wife. The wife, in turn, empties herself in the act of submission to her husband so that there is nothing in her that is self-centered. She acts purely in love for her husband. The beauty here--and the implicit critique of systems which are overly concerned with assigning rights--is that the focus and the blessing here is not on who has authority but on who is the greater servant to his or her spouse.

There is no domination in this. No women being treated as children relative to men. There is no concern for authority at all, and the obsession with who is "in charge" is a contemporary battle being waged because we have forgotten that self-sacrifice is a Christian virtue and equal rights a secular one. I do not believe that women should be in the pulpit. I don't pretend to understand why, entirely, Scripture indicates that, but I can see fairly clearly that it does. Certainly, I can imagine a comprehensive Christian theory of gender which validates that viewpoint without creating a value disparity between the sexes. Ultimately, if there is some person (of either gender) out there who is indignant over his or her inability to rise through the ecclesiastical ranks of power, my concern is not with whether or not the individuals rights are being protected but with whether or not that person (and our church culture as a whole) has a firm enough grasp on the central tenets of the Christian ethos. We certainly ought to stand up for what is right and there are battles worth waging. It is my belief, however, that more pernicious than the threat of patriarchy--which I contend our culture has put aside in all its darkest forms--is that of self-motivated ambition and the undeserved sense of entitlement. Without putting too much rhetorical weight on it, I dare say that rather than lamenting the prospect of women being treated like children we ought to all rejoice at the idea that we may humble ourselves and become like children so as to enter the kingdom of heaven.

________________________________________________________________________

I suppose there is very little to offend in my previous thoughts about the theoretical value of understanding men and women as different but equal. After all, even Dr. Olson admits that to one degree or another this is a universally recognized truth. What was controversial, and will be addressed at greater length here, is the suggestion that those difference cannot be neatly compartmentalized into the incidences of anatomy. There are, to put it crudely, substantial economic distinctions between males and females that cannot be reduced into prescriptions about whether God intended semen to come out of your or go into you. It is a tragic inevitability that more time should need to be spent on this latter fact than on the former, since the truth that God is a God who delights in constructive difference ought to be (and in my experience is) the focal point of complementarian thought. I regret that by focusing on the secondary, pragmatic aspects of complementarianism I legitimize, in a sense, Olson's complaint that for complementarians the "emphasis is not on males and females complementing each other but on females being submissive to males." Yet it should be recognized that this criticism is self-propagating. After all, if egalitarians and complementarians disagreed about value and function rather than on women in the pulpit then the conversation would be dominated by the former issue and the latter would be ignored. It is out of polemical necessity more than anything else that the debate has been translated from the core issues into mere accidents. Insofar as complementarians through repetitive arguments and microscopic focus on application forget to stress the essential truths of what is a more comprehensive anthropology, that shortcoming is ours as humans not a flaw in the truths which we feel compelled to express.

With that said, the other shoe is ready to drop. I believe that wives should submit to their husbands and that women should not exercise authority over men in the congregation. These do not encapsulate my complementarian beliefs, but they are nevertheless an undeniable product of them. From here, there are countless directions I could go. I might attempt to counter Olson's assertion that only unabashed and "never really consistently" literalism can produce complementarian readings of Scripture by pointing out how theologically dangerous it is to excise under the guise of "cultural particularity" commands which are rooted in creation and yoked with soteriology. I could talk about the countless other social norms which Jesus and Paul were willing (even eager) to transgress and contrast it with their marked reluctance to do so with certain features of gender economics. I could trace the full and rich biblical picture of complementarian gender relations as they are depicted as fruitful and righteous throughout Scripture, demonstrating a marked consistency between Old and New Covenant gender economics. But I won't, in large part because my point here is not to prove complementarianism. It is to demonstrate that there can be and are complementarians whose interests lie beyond (and even exclude) the end of subjugating women, to correct Olson's egregious characterization that in complementarianism "adult women have pretty much the same role as children vis-à-vis adult men."

Ultimately, I think the concern most egalitarians express (by which, I of course mean the revulsion most egalitarians feel) regarding complementarianism is born out of a capitulation to modern ideas of rights, authority, and power. In essence, there is a suggestion that unless women are given authority, they are somehow devalued. Unless they are presented with a full compliment of rights, they are second-class citizens. Unless they have power, they are helpless and destined for abuse (a specter Olson proves all to eager to conjure). In short, it is hard not to be left with the impression that, whether consciously or unconsciously, many egalitarians have bought into the anthropology of a post-nietzschean West which glorifies the will to power. If women are fully human they must have the opportunity to pursue their ambition to seize the highest clerical offices, command the most powerful pulpits, vie for control in their marriages, and to become the Übermensch (rather than, as in Nietzsche, simply to birth the Übermensch).

Egalitarians, I imagine, would balk at that depiction of their beliefs and particularly its marriage to so dark a figure as Nietzsche. (Though, for my part, I find it less offensive a picture than that of complementarians as domineering patriarchs seeking eagerly to have paternal authority over all 3.5 billion women in the world.) Certainly, I am open to the idea that the above has at least as much rhetorical flourish as it does substance. Egalitarians would surely not debate, however, that there motivating impulse is equal rights, rich as that term is with savory left-wing utopian connotations. The problem arises, however, in that I don't believe in rights. I don't believe we have them, and I certainly don't think it is expressive of the Christian ethos to pursue them for ourselves. The quest for power, authority, and rights--which I will from here on collapse into the concept of authority, since it is primarily the right to have authority and the power derived from it on which the debate centers--is found nowhere in the Gospel. Instead, all authority is derived from God and given, qualified as it is, as a gift from Him. It is not a right to be seized but a commission to be accepted.

Instead, the Gospel is a narrative of submission and self-sacrifice. Jesus Christ, to whom all authority had been given, is the prime example of this. Consider the way he exercised his authority throughout his ministry. It was not in dictatorial commands to his disciples (male or female). It was not in domination over them. Instead, he assumed the role of a servant: feeding the hungry, encouraging the downtrodden, forgiving the sinner, and washing the feet of his disciples. The same ethos will carry into the earliest church. Though we occasionally see Paul making appeals to his authority (acknowledging always its derivative nature), the overwhelming example given by the apostles is one of unqualified service and the exhortation for Christians to do the same. Christ foreshadows and Paul recalls the cross as the central image of power, ironically redefined by the Gospel, for the whole Christian system. It is in dying the Christ ultimately defeats death and in our participation in that self-sacrificial act that Christians ultimately free themselves from it. Christian virtue is defined by and emulates this core self-sacrificial act. It does not strive after positions of power; it deliberately eschews them, allowing Christ to become a new kind of king. If our understanding of authority--its scope and function--were genuinely cruciform, then the Bible could place women in a perpetual and inviolable state of servitude and, far from making their position lamentable, it would glorify them in so doing.

Of course, it doesn't and no self-respecting complementarian thinks that it does. The biblical picture of gender economics is one of mutual self-sacrifice and voluntary submission, because the virtues embodied in the cross are by no means exclusive to one sex. The most complete and wonderful picture is in the much maligned household codes in Ephesians, which gives two interrelated commands: wives submit to your husbands (as the church submits to Christ) and husbands sacrifice yourself for your wife (as Christ sacrificed himself for the church). It is important first to note that all submission and self-sacrifice is related directly back to Christ as the exemplar. It is not the Christ came and made himself a servant because he was less than those he came to serve. He humbled himself in spite of his superiority. Moreover, Christ did not sacrifice himself as it suited him and to the degree it suited him but completely and in ways which most profoundly effected him. What is depicted in the relationship between Christ and the church is not the degree of authority which is being conferred upon husbands but the nature of the relationship. What is being prescribed for wives and husbands is, in its essence, a common disposition toward one another. After all, Christians are exhorted to submission (the same kind of submission that wives are specifically enjoined to choose) to all other Christians in the verse immediately prior. The image is of a husband who empties himself in the act of sacrifice for his wife so that there is nothing in him that self-centered. He acts purely in love for his wife. The wife, in turn, empties herself in the act of submission to her husband so that there is nothing in her that is self-centered. She acts purely in love for her husband. The beauty here--and the implicit critique of systems which are overly concerned with assigning rights--is that the focus and the blessing here is not on who has authority but on who is the greater servant to his or her spouse.

There is no domination in this. No women being treated as children relative to men. There is no concern for authority at all, and the obsession with who is "in charge" is a contemporary battle being waged because we have forgotten that self-sacrifice is a Christian virtue and equal rights a secular one. I do not believe that women should be in the pulpit. I don't pretend to understand why, entirely, Scripture indicates that, but I can see fairly clearly that it does. Certainly, I can imagine a comprehensive Christian theory of gender which validates that viewpoint without creating a value disparity between the sexes. Ultimately, if there is some person (of either gender) out there who is indignant over his or her inability to rise through the ecclesiastical ranks of power, my concern is not with whether or not the individuals rights are being protected but with whether or not that person (and our church culture as a whole) has a firm enough grasp on the central tenets of the Christian ethos. We certainly ought to stand up for what is right and there are battles worth waging. It is my belief, however, that more pernicious than the threat of patriarchy--which I contend our culture has put aside in all its darkest forms--is that of self-motivated ambition and the undeserved sense of entitlement. Without putting too much rhetorical weight on it, I dare say that rather than lamenting the prospect of women being treated like children we ought to all rejoice at the idea that we may humble ourselves and become like children so as to enter the kingdom of heaven.

Labels:

complementariansim,

cross,

gender economics,

rights,

Roger E. Olson,

service

Friday, February 10, 2012

Complementarianism: Value and Function

The following is part of an ongoing response to Roger E. Olson’s critique of extreme complementarianism. For the origin and nature of these posts, see Complementarianism: A Defense from a Nobody.

________________________________________________________________________

I imagine that many, perhaps even Dr. Olson (who, while a real person, has taken on for my purposes here more the role of a fictional foil against which to cast complementarianism), consider the distinction between value and function as far as gender economics is concerned to be a thin veneer behind which to hide overt sexism. The distinction is, nevertheless, one which I believe to be substantive and necessary for approaching the question of gender economics. In simpler terms, it is the philosophical underpinning for the idea that things can be different but equal. That phrasing has the nasty connotation of racist ideals of “separate but equal” which were in fact merely a façade for separate and deeply unequal treatment. The problem both with “separate but equal” and the distinction between value and function is not in the abstract but in the improper application.

Distinguishing function from value is an assumption that we all operate with uncritically with on a daily basis. For example, consider the question, “Who do you love more, your spouse or your children?” Even as someone without children, I realize that question is nonsensical. The only appropriate, healthy answer is, “I love them equally.” And yet, you do not have the same expectations from your spouse as you do your children. You value them equally and yet you recognize that there is a fundamental difference in the way they operate relative to you. In theory then, at least, I hope everyone can agree to the possibility of ontological equality and economic distinction.

Even Olson admits that essentially everyone agrees that men and women were created for different functions. After all, it is hard not to look at a male and a female and realize that they are not quite the same. On the other hand, Olson’s only practical example of this is to point to anatomical distinctions: “even feminists believe men and women have different roles insofar as only women give birth!” At the core of complementarianism, however, is the belief that God chose to create men and women with more important differences than the ability of men to urinate standing up.

In fact, an appeal to pregnancy—or anatomy more generally—as a key functional difference between men and women seems to treat the problem in reverse. It forgets, in essence, that God was not constrained by the world He had not yet created and the reproductive strictures He would produce. In other words, there was nothing preventing God from creating a vast hermaphroditic biosphere in which there is neither maleness nor femaleness. For that matter, He might just have easily have made all life reproduce by mitosis and save us all the trouble of coupling to begin with. For my part, this realization of divine freedom calls into question any model of gender economics which asks how men and women are different and turns to anatomy for the crucial answers. Instead, we ought to ask, “Given that men and women are obviously biologically different: why?”