At the September 5th

Palmetto Freedom Forum, Ron Paul gave a not unsurprising glimpse into the historiographical paradigm which he believes governs all of history. In an introductory speech on the first principles of American government, Paul commented, "If we believe in liberty, we have to also understand exactly what our revolution was all about, because the contest then, at that time, was against tyranny--as all history has been, tyranny versus liberty." In the sweeping declaration of his final clause, Paul readily admits the prism through which he understands human history and the context in which he places his own struggle for reform.

Christianity, for its part, has proposed more dominant and enduring historiographical paradigms, the most popular of which has been the Fall-Redemption paradigm which has dominated Western thought at least since the time of Anselm and which found a profound invigoration from the dominance of Calvinism in Protestant culture. Panayiotis Nellas has proposed that, alternatively, Eastern Christendom has operated with a Creation-Deification paradigm for understanding history, which I find to be a superior system at least for understanding the overarching and decidedly metaphysical understand Christians have of history. It is clear to me, however, the Paul is not proposing so much of an ideological paradigm for understanding all of history so much as he is proposing a system for understanding the history of human governance. Christianity has a corrective answer for this as well.

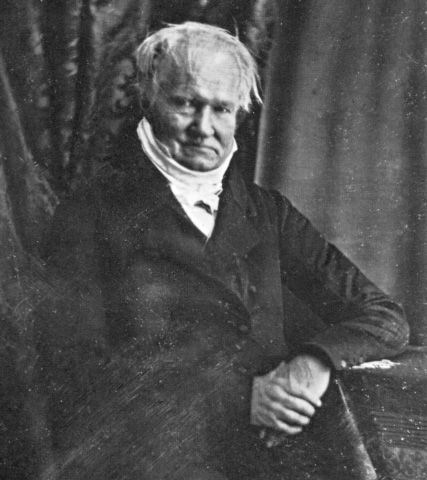

Notably,

David Lipscomb, would have objected to a characterization in which history could be reduced to a struggle for liberty against tyranny in which, Paul believes, the early days of America were the "best taste of liberty ever." Quite the opposite, Lipscomb insisted that America no less than any other civil government in history was an evil, violent, coercive institution which had set itself up in an arrogant attempt to usurp the governing authority of God. In contrast, Lipscomb proposed a Christian historiography which was best understood, not as a battle between liberty and tyranny, but instead a struggle between liberty and autonomy. Such a juxtaposition grates against our modern sense of freedom which considers "liberty" and "autonomy" to be near synonyms.

Embracing this modern construction of liberty, Paul appeals to the founding fathers: "Thomas Jefferson was very clear about liberty and he told us where liberty came from. It came from our creator; it didn't come from our government." While Paul clearly interprets the Declaration of Independence the way Jefferson intended it to be read, there is a hidden irony in the declaration that liberty comes from God. For Christians, freedom is not libertinism and it is not autonomy. Freedom is a freedom to actualize human potential, to become that which God in His infinite and beneficent wisdom has ordained for all of us. Liberty is a liberation from the

evils of this world that would enslave and entangle us. That is why Paul (the apostles, not the politician) can

in the same breath speak of being free and being a servant to all; it is why Peter can

boldly declare that Christians are a free people and still slaves to God; it is why the psalmist can

draw a causal connection between being free and being obedient.

It is this kind of freedom, secured by God and not by civil government, which is the truly substantial form of liberty and which can never be taken away. When we remember that it is

the truth that sets us free and not a republican political ideal, we begin to see the flaws in Congressman Paul's historiography. History has not been, cannot have been the struggle between freedom and the rule of tyrannical governments because in truth liberty eschews all self-rule, whether it is "tyrannical" by Paul's standards or not. Political history is the sordid tale of humanity crying out for self-rule and then chaffing under their own structures of power, of Israel demanding of God a king and then having that royal house lead the charge into political, social, and religious chaos. Only when we embrace this historiography (insofar as it applies) can we begin to correct the modern Christian approach to self-government, both politically and personally. Perhaps then we can baptize and embrace another

Jeffersonian principle and avoid entangling alliances between those governed by God and those pursuing

self-rule. Or, in the rougher parlance of my former history professor, it is time to realize that when church and state get into bed together, inevitably it is the church who plays the whore.