[…], by far the greatest anatomist of the age, used to say that he could distinguish in the darkest room by one stroke of the scalpel the brain of the inebriate from that of a person who lived soberly. Now and then he could congratulate his class upon the possession of a drunkard’s brain, admirably fitted from its hardness and more completed preservation for the purpose of demonstration. When the anatomist wishes to preserve a human brain for any length of time, he effects that object by keeping that organ in a vessel of alcohol. From a soft pulpy substance , it then becomes comparatively hard, but the inebriate, anticipating the anatomist, begins the indurating process before death, begins it while the brain remains the consecrated temple of the soul while, while its delicate and gossamer-like tissues still throb with the pulse of heaven-born life. Strange infatuation this, to desecrate the God-like. Terrible enchantment that dries up all the fountains of generous feelings, petrifies all the tender humanities and sweet charities of life, leaving only a brain of lead and a heart of stone.

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Some Standard Wisdom on Brain Pickling

One of the recurrent themes in the articles that caught my eye while reading through the 1880 editions of the Christian Standard was the confidence with which they trumpeted the scientific knowledge of their day. Looking at the science of a bygone era, in edition to being tremendously amusing, ought to give us pause today about our own scientific hubris and force us to wonder how future generations will perceive our cutting-edge thought, particularly as it filters down to the popular level. This piece was copied by the Standard from Scientific American, which is still in publication.

Labels:

alcohol,

Christian Standard,

nineteenth century,

quotes,

science

Friday, May 17, 2013

Creation vs. Evolution vs. Catholicism

The Barna Group, commissioned by BioLogos, has just released an intriguing new study about sharp divides among "today's pastors" about science, faith, and the origin of species. The study shows an almost even split between those who believe in Young Earth Creation and those who do not, with the do not group being divided between proponents of theistic evolution and progressive creationism. Young Earth Creationists have their stronghold in the South, while theistic evolution is most common in the Midwest. Most clergy think that questions of faith and science are important, but, at the same time, a majority fear that disagreements are distracting from the greater Christian witness.

There is little there to shock, unless you realize one glaring omission: Catholics. While the survey of Protestant ministers actually excludes both Orthodox and Catholic leaders, the Orthodox have only about one million members in the United States, making their omission excusable (at least from a statistician's point of view). Catholics, on the other hand, are no minority to be trifled at. As the largest single Christian denomination in the United States--one in four Americans belongs to the Roman Catholic Church--their absence from a survey about the origins of life suggests an array of possible biases, all of them disturbing. It is likely that, in lockstep with history, that Catholics are still being treated as second class Christians or (perhaps implicitly) not real Christians at all. It would not be the first time the self-proclaimed Protestant establishment drew a sharp line between Christianity and papism--even if it can no longer express the dichotomy in those terms in our politically correct age. Equally possible, Catholics may have been excluded because their presumed answers would have tipped the scale away from a picture of conflict between conservative and progressive thought on origins. The Roman Catholic Church never engaged in the kind of systematic anti-evolution campaigns that so many Protestants did at the turn of the twentieth century in response to Darwin. In fact, for more than sixty years the official Catholics position has been that there is no conflict between evolution and Christianity, leading to a de facto triumph of theistic evolution among leading Catholic divines. Admitting Catholics into the dialogue would throw off both the slim majority of Young Earth Creationists and the geography of creationism (with the South and Southwest being an area of significant Catholic presence).

Or maybe the Barna Group just never thought to include Catholics. But would that really be better?

There is little there to shock, unless you realize one glaring omission: Catholics. While the survey of Protestant ministers actually excludes both Orthodox and Catholic leaders, the Orthodox have only about one million members in the United States, making their omission excusable (at least from a statistician's point of view). Catholics, on the other hand, are no minority to be trifled at. As the largest single Christian denomination in the United States--one in four Americans belongs to the Roman Catholic Church--their absence from a survey about the origins of life suggests an array of possible biases, all of them disturbing. It is likely that, in lockstep with history, that Catholics are still being treated as second class Christians or (perhaps implicitly) not real Christians at all. It would not be the first time the self-proclaimed Protestant establishment drew a sharp line between Christianity and papism--even if it can no longer express the dichotomy in those terms in our politically correct age. Equally possible, Catholics may have been excluded because their presumed answers would have tipped the scale away from a picture of conflict between conservative and progressive thought on origins. The Roman Catholic Church never engaged in the kind of systematic anti-evolution campaigns that so many Protestants did at the turn of the twentieth century in response to Darwin. In fact, for more than sixty years the official Catholics position has been that there is no conflict between evolution and Christianity, leading to a de facto triumph of theistic evolution among leading Catholic divines. Admitting Catholics into the dialogue would throw off both the slim majority of Young Earth Creationists and the geography of creationism (with the South and Southwest being an area of significant Catholic presence).

Or maybe the Barna Group just never thought to include Catholics. But would that really be better?

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

Some Standard Wisdom for Avoiding Epidemics

Continuing with the theme of amusing ourselves at the expense of the level of scientific and technical knowledge in 1880, the Christian Standard published extensive quotes from and commentary on an article by E. W. Cushing which first appeared in the International Review:

We are apparently on the climax—which arrives in 1882—of a cycle of epidemics, which coincides with the sun spots of some eleven years and a fraction. As he argues, it is a time of great disturbances in temperatures, etc….After a carefully prepared table of the great epidemics known in history, which are shown to correspond very clearly with the semi-changes, he concludes: “Now what can these general influences be, this general cause, this morbific influence of an unknown nature? Does the earth itself change periodically? No. Does the mass of air or water change? No. What can change them? The force, the heat, the energy which is derived directly from the sun. Does this change regularly, periodically, and at intervals corresponding with those of this pestilence? It certainly does; and all these strange natural phenomena which we have seen to have been observed in all ages as the forerunners or accompaniments of epidemics are now known to depend on, or at least to coincide with, the changes of solar energy corresponding with the sun spot cycle. Here is certainly the post hoc; shall we not admit the propter hoc?”

Depending on what the fraction is in "eleven years and a fraction," I fear we may be due for another period of epidemic disease in 2013. Oh wait.

Labels:

astronomy,

Christian Standard,

disease,

E. W. Cushing,

medicine,

nineteenth century,

quotes,

science

Friday, March 22, 2013

The Question of Extraterrestrial Life (less than) Definitively Settled

I am inclined to think that there is no life on other planets. I have heard repeatedly the statements about the sheer size of the universe and the correlative theoretical quantity of planets, among which it is as near a statistical certainty as possible that many can support life and consequently that one does. Yet precisely this mathematical certainly disinclines me to believe that there is life beyond Earth. I am not saying that there isn't or that it would bother me if there were; only that I am choose not to suppose that there is.

I am inclined to think that there is no life on other planets. I have heard repeatedly the statements about the sheer size of the universe and the correlative theoretical quantity of planets, among which it is as near a statistical certainty as possible that many can support life and consequently that one does. Yet precisely this mathematical certainly disinclines me to believe that there is life beyond Earth. I am not saying that there isn't or that it would bother me if there were; only that I am choose not to suppose that there is.The reason is, therefore, clearly not rational. It is not, however, strictly speaking irrational, which would imply a failure to rationally derive an argument for a proposition. Instead, it is contrarational. Having divined and accepted the rational argument that there is life on other planets, I formulate my belief in conscious opposition to that. What justifies such a contrarational position? It is precisely that beauty, joy, sublimity (or some other vague and subjective term) exist in contrast to rationality.

Again, this is not to say that the rational cannot be beautiful or incite joy or embody the sublime. It merely acknowledges what has been a well recognized feature of art and literature and romance and life. The human spirit is enlivened more by the unpredictable, the unexplainable, and the impossible-but-actual than by the reasonable. Serendipity and providence. Mad, stupid, consumptive, doomed love. Fantasies and phantasmagoria and psychosis.

I believe in a beautiful God, one Who transcends and can therefore contradict reason. The notion that this foolish Deity could have created a world which by its very nature speaks to the mathematical certainty of life on other plants and then refuse to populate any planet but this one fills me with an inexplicable joy in the mere possibility of it. I will rejoice in a God who creates and saves the inhabitants of other worlds as well, but until I know otherwise I prefer to be seized by the sublime belief in a universe that must and a God who flouts such necessity.

Labels:

aesthetics,

contrarationalism,

extra-terrestrials,

joy,

logic,

mathematics,

reason,

science,

sublime

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Moore on Science

In his landmark book Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans, Laurence Moore reflected on the tendency of the American media to periodically declare that occultism is on the rise. The charge of press sensationalism is not new--and not his point. Instead, looking back to the "occult" religious sects of the 19th century, he makes an intriguing point about the myth of secularization through science:

The American press likes to announce occult revivals in which Americans react against the world view of "modern science." Yet the journalistic emphasis on ebb and flow seems much overdone. The truth is that we do not live in an uncomplicatedly secular age. The scientific revolution, wherever in time one wants to cut into it, has promoted in almost equal parts a respect for empiricism among experimental scientists and a more popular belief that experiment can push beyond the limits of ordinary sensory awareness...

[This way of thinking], rather than being rendered archaic by scientific and technical progress, has, like science fiction, often gained credibility among those who have welcomed that progress. The people who believe in ESP, after all, do not think of themselves as Criticizing science per se. In their minds, they are merely urging science to stretch beyond the materialistic assumptions that proscribe certain types of research.

Labels:

Christian Science,

ESP,

quotes,

R. Laurence Moore,

science,

secularity,

the occult

Sunday, January 20, 2013

History for History's Sake

In his 1969 article, "Second Thoughts on History at the Universities," British historian Sir Geoffrey Elton made the following recommendation:

Elton's view is likely to win at least public support from many academic historians, as much as it is equally likely to elicit public scorn from just about everyone else, particularly those outside of the humanities (and of those particularly scientists for whom usefulness is assumed, in the discipline if not always in the particular research project). Yet, in truth most historians today go to great lengths to contort themselves and their work to conform to expectations of social relevance. Every new paper, every new book is subjected to one degree or another to questions not just of how it advances human knowledge but how it might benefit human society. Most defenses are theoretical and superficial, but that they must be made at all reveals something.

It would be easy, not to mention self-serving, for me to now turn and defend a universal application of Elton's advice that history be pursued without regard for usefulness. After all, I have spent most of my admittedly short academic career studying the most utterly useless facts jotted into the marginalia of history. The more esoteric, the more alluring. But critics of the humanities in general and history in particular are largely correct. Rightly gone are the days when the government could and would subsidize the pursuit of knowledge of the sake of knowledge, particularly knowledge which has no clear future applicability. History is, in this respect, the worst academic offender.

Yet Elton is correct when his own language is allowed to limit the scope of his observation. The above are from reflections on "history at universities" and directed at "teachers of history." As history continues to be rightly scrutinized for its social value, it is important not to transfer criticisms of professional historians onto the discipline as a whole. Historical thinking--rather than the academic fruits of the professionalized application of historical thought--is in fact a necessary tool. It has been rightly observed that all humans are historical thinkers, existing as much in their reflection on their individual (and on our collective social) past as they do in the present. The "standards of judgment" and "powers of reasoning" that characterize self-conscious historical thought are crucial tools in the continued functioning of our species. If we allow our critique of ivory tower academics to come to bear on the general curriculum--in universities, but also in high school or middle school as well--then we jeopardize the intellectual future of our children.

It is not uncommon now--and this is true both of where I went to school and of the university I work for now--that undergraduates can be expected to take more than twice as much science as history, regardless of their intended field. The deeply incorrect assumption here is that people on average will need more biology in their lives than, for example, American history, more familiarity with chem-lab safety protocol than the causes and consequences of the communist revolution in China. The devaluing in the public mind of history, abetted as it has been by the increasing specialization in the discipline (e.g. a professor I know who studies only the history of agricultural technology in the plantation South), is poised to create a generation of historically and culturally illiterate actors, agents in the making of our ongoing history.

Teachers of history must set their faces against the necessarily ignorant demands of 'society'...for immediate applicability. They need to recall that the 'usefulness' of historical studies lies hardly at all in the knowledge they purvey and in the understanding of specific present problems from their prehistory; it lies much more in the fact that they produce standards of judgment and powers of reasoning which they alone develop which arise from the very essence, and which are unusually clear-headed, balanced and compassionate.

Elton's view is likely to win at least public support from many academic historians, as much as it is equally likely to elicit public scorn from just about everyone else, particularly those outside of the humanities (and of those particularly scientists for whom usefulness is assumed, in the discipline if not always in the particular research project). Yet, in truth most historians today go to great lengths to contort themselves and their work to conform to expectations of social relevance. Every new paper, every new book is subjected to one degree or another to questions not just of how it advances human knowledge but how it might benefit human society. Most defenses are theoretical and superficial, but that they must be made at all reveals something.

It would be easy, not to mention self-serving, for me to now turn and defend a universal application of Elton's advice that history be pursued without regard for usefulness. After all, I have spent most of my admittedly short academic career studying the most utterly useless facts jotted into the marginalia of history. The more esoteric, the more alluring. But critics of the humanities in general and history in particular are largely correct. Rightly gone are the days when the government could and would subsidize the pursuit of knowledge of the sake of knowledge, particularly knowledge which has no clear future applicability. History is, in this respect, the worst academic offender.

Yet Elton is correct when his own language is allowed to limit the scope of his observation. The above are from reflections on "history at universities" and directed at "teachers of history." As history continues to be rightly scrutinized for its social value, it is important not to transfer criticisms of professional historians onto the discipline as a whole. Historical thinking--rather than the academic fruits of the professionalized application of historical thought--is in fact a necessary tool. It has been rightly observed that all humans are historical thinkers, existing as much in their reflection on their individual (and on our collective social) past as they do in the present. The "standards of judgment" and "powers of reasoning" that characterize self-conscious historical thought are crucial tools in the continued functioning of our species. If we allow our critique of ivory tower academics to come to bear on the general curriculum--in universities, but also in high school or middle school as well--then we jeopardize the intellectual future of our children.

It is not uncommon now--and this is true both of where I went to school and of the university I work for now--that undergraduates can be expected to take more than twice as much science as history, regardless of their intended field. The deeply incorrect assumption here is that people on average will need more biology in their lives than, for example, American history, more familiarity with chem-lab safety protocol than the causes and consequences of the communist revolution in China. The devaluing in the public mind of history, abetted as it has been by the increasing specialization in the discipline (e.g. a professor I know who studies only the history of agricultural technology in the plantation South), is poised to create a generation of historically and culturally illiterate actors, agents in the making of our ongoing history.

Labels:

education,

higher education,

history,

quotes,

science,

Sir Geoffrey Elton

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

The Wisdom of Alexander von Humbodlt

Alexander von Humboldt was once among the most famous names in all America, a fact testified to by the dozens of cities, rivers, bays, and species that were named after him. An explorer, commentator, and philosopher, he is best remembered today, if he is remembered at all, as the father of the 19th century scientific movement that bears his name and stresses the interrelatedness of the various aspects of nature and of humanity and nature.

More interesting to me, however, are these comments he made about liberty in America. For as strong as America's love was for Humboldt--and for a time Humboldt returned that affection, particularly through a personal friendship with Thomas Jefferson--Humboldt proved himself a willing and able critic of American hypocrisy. At a time when the American rhetoric about liberty was its most eloquent and its failure to live up to that rhetoric most obvious, Humboldt made this observation:

Americans are less philosophical in their ideals and less overt in their failure to live up to them, but I suspect that Humboldt's criticism remains largely accurate.

More interesting to me, however, are these comments he made about liberty in America. For as strong as America's love was for Humboldt--and for a time Humboldt returned that affection, particularly through a personal friendship with Thomas Jefferson--Humboldt proved himself a willing and able critic of American hypocrisy. At a time when the American rhetoric about liberty was its most eloquent and its failure to live up to that rhetoric most obvious, Humboldt made this observation:

In the United States there has, it is true, arisen a great love for me, but the whole there presents to my mind the sad spectacle of liberty reduced to a mere mechanism in the element of utility, exercising little ennobling or elevating influence upon mind and soul, which, after all, should be the aim of political liberty. Hence indifference on the subject of slavery. But the United States are a Cartesian vortex, carrying everything with them, grading everything to the level of monotony.

Americans are less philosophical in their ideals and less overt in their failure to live up to them, but I suspect that Humboldt's criticism remains largely accurate.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

The Wisdom of Niels Bohr

I recently came across this quote from Niels Bohr in an environmental history of the United States. It is apparently quite a famous quote, but, not being a scientists, it was entirely new to me. Here, succinctly, one of the greatest physicists in history accurately removes science from essentialist pursuits and relegates it to its proper, observational sphere:

It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about nature

Monday, November 12, 2012

Cow News

If you thought the story, previously shared, of cows producing lactose-free milk was astonishing, just wait until you see what these magnificent creatures are doing now:

Got milk?

Would protection against the deadly human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) make you willing to give up your vegan lifestyle? New research from Australia’s Melbourne University suggests that a type of treated cow’s milk could provide the world’s first HIV vaccine.

Working together with biotechnology company Immuron Ltd., the Australian research team vaccinated pregnant dairy cows with an HIV protein. This injection posed no risk to the cows, as they are unable to contract the disease, according to researchers. After giving birth, the first milk produced by the cows was found to contain HIV-disabling antibodies...

“We were able to harvest antibodies specific to the HIV surface protein from the milk,” said Dr. Marit Kramski, who is presenting her research as one of the winners of Fresh Science — a national program for early-career scientists. “We have tested these antibodies and found in our laboratory experiments that they bind to HIV and that this inhibits the virus from infecting and entering human cells,” she said.

Got milk?

Labels:

AIDS,

cows,

disease,

HIV,

Immuron Ltd.,

Marit Kramski,

medicine,

news,

science

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Lactose Free Cows?

New Zealand researchers have genetically engineered a cow whose milk, produced for the moment by artificially stimulated lactation, lacks β-lactoglobulin protein, one of the primary milk allergens affecting humans. Great news for people who are lactose intolerant!

Or not, since apparently it is presently illegal to market or even consume transgenic milk. There are perhaps more important reasons to take the linked story as less than the revolutionary news the headlines make it out to be. For example, the researches can't explain the curious rise in casein proteins in the milk. They also are dismissing as irrelevant--though unconvincingly--the premature birth of their franken-cow and the significant absence of Daisy's tail. (Perhaps Eeyore has it.)

If only there were a way for lactose intolerant people to survive, even thrive, without scientists amusing themselves by tinkering with the genetic makeup of cows. If only we could get baby cows the old fashioned way, the way God intended. Using smart phones.

Or not, since apparently it is presently illegal to market or even consume transgenic milk. There are perhaps more important reasons to take the linked story as less than the revolutionary news the headlines make it out to be. For example, the researches can't explain the curious rise in casein proteins in the milk. They also are dismissing as irrelevant--though unconvincingly--the premature birth of their franken-cow and the significant absence of Daisy's tail. (Perhaps Eeyore has it.)

If only there were a way for lactose intolerant people to survive, even thrive, without scientists amusing themselves by tinkering with the genetic makeup of cows. If only we could get baby cows the old fashioned way, the way God intended. Using smart phones.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

The Wisdom of Mark Twain

The following quote from Mark Twain's Life on the Mississippi has a tendency to appear in a variety of contexts, from discussions of mathematical principles to misguided attempts to defend creationism. I recently encountered it employed by Anna Green and Kathleen Troup as part of a critique of some of the possible excesses of quantitative history. Regardless of the context, it is simultaneously humorous and thought provoking as only Twain is:

Therefore: the Mississippi between Cairo and New Orleans was twelve hundred and fifteen miles long one hundred and seventy-six years ago. It was eleven hundred and eighty after the cut-off of 1722. It was one thousand and forty after the American Bend cut-off (some sixteen or seventeen years ago.) It has lost sixty-seven miles since. Consequently its length is only nine hundred and seventy-three miles at present.

Now, if I wanted to be one of those ponderous scientific people, and "let on" to prove what had occurred in the remote past by what had occurred in a given time in the recent past, or what will occur in the far future by what has occurred in late years, what an opportunity is here! Geology never had such a chance, nor such exact data to argue from! Nor "development of species," either! Glacial epochs are great things, but they are vague--vague. Please observe:

In the space of one hundred and seventy six years the Lower Mississippi has shortened itself two hundred and forty-two miles. That is an average of a trifle over one mile and a third per year. Therefore, any calm person, who is not blind or idiotic, can see that in the Old Oölitic Silurian Period, just a million years ago next November, the Lower Mississippi River was upwards of one million three hundred thousand miles long, and stuck out over the Gulf of Mexico like a fishing-rod. And by the same token any person can see that seven hundred and forty-two years from now the Lower Mississippi will be only a mile and three quarters long, and Cairo and New Orleans will have joined their streets together, and be plodding comfortably along under a single mayor and a mutual board of aldermen. There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.

Labels:

geography,

Mark Twain,

Mississippi River,

quotes,

satire,

science

Friday, April 27, 2012

Evolution is a Myth!

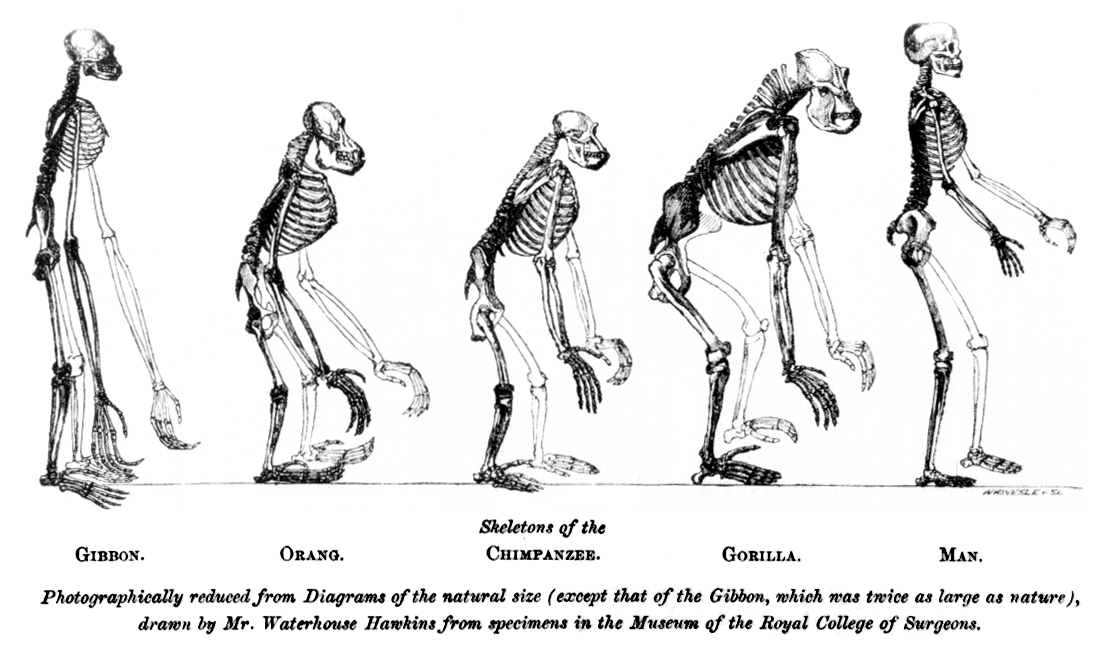

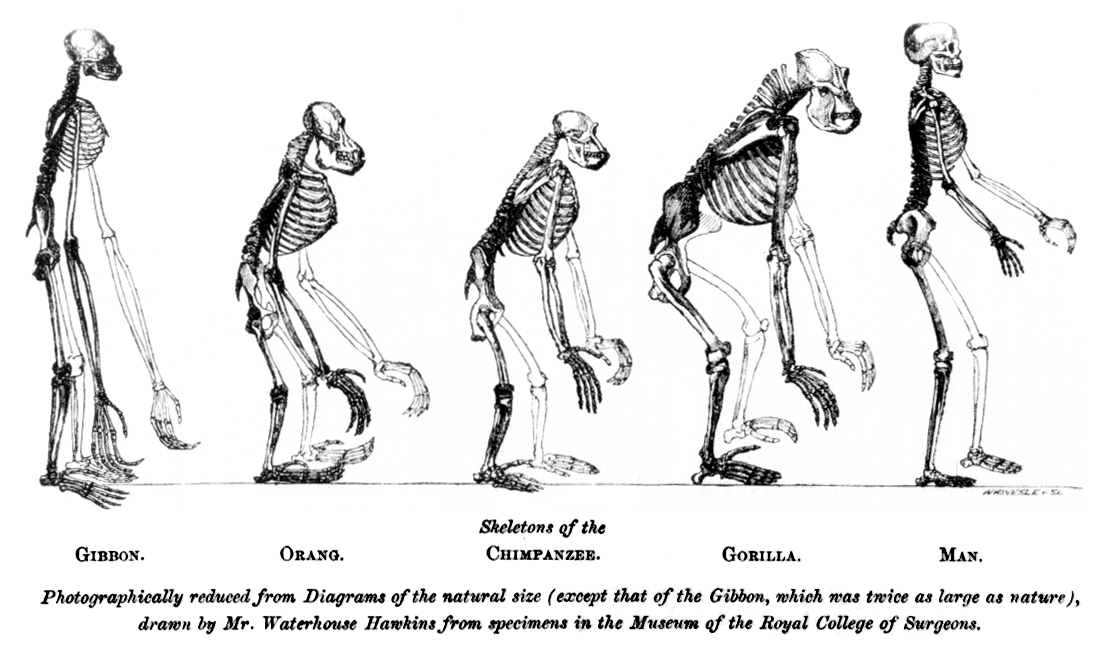

That is the incendiary and intriguing claim of physicist Hugh Henry and biblical scholar Daniel J. Dyke in their joint 2010 article "Evolution as Mythology." The purpose of their paper is not to call into question the factual accuracy of evolution (as the colloquial definition of "myth" might imply), and both authors accept evolution as a valid scientific theory (without any of the tentativeness that the colloquial definition of "theory" might imply). Henry and Dyke do not examine evolution primarily with the aim of evaluating whether or not it is true, and when they critique the science of evolution it is never with the purpose of debunking it in favor of a more religiously palatable excuse. Instead, the authors are interested only in examining whether or not evolution functions in Western culture as a myth in a sociological sense.

It is prudent here, and the authors recognized the need, to define more clearly how myth is used so as to avoid any confusion which the everyday use of the term might provoke. Henry and Dyke begin simply with a dictionary definition of myth: "A traditional, typically ancient story dealing with supernatural beings, ancestors, or heroes that serves as a fundamental type in the worldview of a people,

as by explaining aspects of the natural world or delineating the psychology, customs, or ideals of society." They refine this further by appealing to a definition out of comparative religion: "Myths [are] the symbolic stories that communities use to explain the universe and their place within it. . . . Myths are not falsehoods or the work of primitive imagination; they . . . [form] a sacred belief structure that supports the laws and institutions of the religion and the ways of the community." Finally, they expand further on these ideas to complete their own definition: "Mythology serves an important sociological purpose. It explains the world-view of a culture or peoples. It validates the thinking, practices, and ideals of a culture. A creation myth explains existence; without a creation myth, a culture or people are without roots and without purpose." In short, myths are those sacrosanct narrative through which a society orders itself.

With this definition in mind, Henry and Dyke attempt to offer a number of characteristic features of myth which may offer parallels to the way the theory of evolution functions in society. They begin with the most common unifying feature, that of a inexplicable or transcendent guiding force. With its tendency to foster atheism, naturalistic theories of evolution would seem to preclude any deity which might fulfill this criteria. Yet, the authors see in the process of natural selection--all-determinative and yet never fully grasped--the kind of godlike entity that gives evolution its mythic character. The authors observe that "whenever something cannot be explained, natural selection is cited with reverence, as if an omnipotent miracle worker." Lest this seem like a polemical exaggeration on their part, they offer up this quotation from evolutionary zoologist Pierre-Paul Grasse: "Chance becomes a sort of providence, which...is not named but which is secretly worshiped." And another from the venerable godfather of abiogenesis, Harold Urey:

Henry and Dyke suggest a number of other parallels with varying degrees of success. They suggest that, like many other governing myths, the theory of evolution has a profit an Charles Darwin. More convincingly, they note that belief in evolution functions in our society as a social and intellectual shibboleth, distinguishing the orthodox from the heterodox in American culture. While the parallels to the Catholic persecution of Galileo are strained (particularly since those stories are themselves more myth than history), they offer more potent allusions to political or academic disaster resulting from criticisms of evolutionary theory, not to mention a broader fear of being ostracized that accompanies even everyday doubts about evolutionary theory. The authors add, from science historian Marjorie Grene, "It is as a religion of science that Darwinism chiefly held, and holds, men's minds. . . . Darwinian theory has itself become an orthodoxy preached by its adherents with religious fervor, and doubted, they feel, only by a few muddlers imperfect in scientific faith."

Somewhere between the credibility of the argument that evolution has a prophet and that it is a social creed is the authors' suggestion that professional evolutionists function as a kind of intellectual clergy for Western culture with a "secret-knowledge-known-only-to-a-select-few."

Having shown the ways the theory of evolution conforms to the sociological notion of myth, the remainder of the article attempts to illustrate how evolutionary theory falls short by science's own self-imposed strictures. Not being a scientist, and not really caring whether or not evolution is good science, I will leave those arguments for anyone who wants to track down the article. What is striking to me is how compelling the overall thesis of the article is, regardless of the strength of the individual arguments. It is hard to look at evolution and not realize just how thoroughly it functions in our culture much in the same way that creation myths have in all cultures previous. It has become "an article of faith and a test of orthodoxy" from which no one in our society can escape. The myth of naturalistic evolution is a necessary construct, whether factually accurate or not, for justifying the naturalism and materialism that prop up Western notions of politics, science, and ethics.

Many of the parallels Henry and Dyke draw are strained, many will find suspect their assertion that evolution is more myth than science (which is really unnecessary to the claim that evolution functions sociologically as a myth), and it is hard not to be critical on a number of levels of the conclusion that "the existence of a Creator-God has much more evidence than the Theory of Naturalistic Evolution." Yet, these deficiencies notwithstanding, Henry and Dyke make an important contribution to Western self-understanding with this article. "Whether it is right or whether it is wrong," naturalistic evolution has proved a powerful myth--arguably the governing myth--in Western culture. This ought to allow us not only to open evolution to more careful scientific critique, which seems to be the authors' aim, but also to cultural critique. Understanding evolution as myth and embracing the iconoclastic postmodern programme, it is paramount that contemporary society begin to reevaluate evolution as a test for orthodoxy in politics, academia, and culture at large. The time has come to consider again the claims of philosopher of science Wolfgang Smith and to actualize their implications:

It is prudent here, and the authors recognized the need, to define more clearly how myth is used so as to avoid any confusion which the everyday use of the term might provoke. Henry and Dyke begin simply with a dictionary definition of myth: "A traditional, typically ancient story dealing with supernatural beings, ancestors, or heroes that serves as a fundamental type in the worldview of a people,

as by explaining aspects of the natural world or delineating the psychology, customs, or ideals of society." They refine this further by appealing to a definition out of comparative religion: "Myths [are] the symbolic stories that communities use to explain the universe and their place within it. . . . Myths are not falsehoods or the work of primitive imagination; they . . . [form] a sacred belief structure that supports the laws and institutions of the religion and the ways of the community." Finally, they expand further on these ideas to complete their own definition: "Mythology serves an important sociological purpose. It explains the world-view of a culture or peoples. It validates the thinking, practices, and ideals of a culture. A creation myth explains existence; without a creation myth, a culture or people are without roots and without purpose." In short, myths are those sacrosanct narrative through which a society orders itself.

With this definition in mind, Henry and Dyke attempt to offer a number of characteristic features of myth which may offer parallels to the way the theory of evolution functions in society. They begin with the most common unifying feature, that of a inexplicable or transcendent guiding force. With its tendency to foster atheism, naturalistic theories of evolution would seem to preclude any deity which might fulfill this criteria. Yet, the authors see in the process of natural selection--all-determinative and yet never fully grasped--the kind of godlike entity that gives evolution its mythic character. The authors observe that "whenever something cannot be explained, natural selection is cited with reverence, as if an omnipotent miracle worker." Lest this seem like a polemical exaggeration on their part, they offer up this quotation from evolutionary zoologist Pierre-Paul Grasse: "Chance becomes a sort of providence, which...is not named but which is secretly worshiped." And another from the venerable godfather of abiogenesis, Harold Urey:

All of us who study the origin of life find that the more we look into it, the more we feel that it is too complex to have evolved anywhere. We believe as an article of faith that life evolved from dead matter on this planet. It is just that its complexity is so great, it is hard for us to imagine that it did.

Henry and Dyke suggest a number of other parallels with varying degrees of success. They suggest that, like many other governing myths, the theory of evolution has a profit an Charles Darwin. More convincingly, they note that belief in evolution functions in our society as a social and intellectual shibboleth, distinguishing the orthodox from the heterodox in American culture. While the parallels to the Catholic persecution of Galileo are strained (particularly since those stories are themselves more myth than history), they offer more potent allusions to political or academic disaster resulting from criticisms of evolutionary theory, not to mention a broader fear of being ostracized that accompanies even everyday doubts about evolutionary theory. The authors add, from science historian Marjorie Grene, "It is as a religion of science that Darwinism chiefly held, and holds, men's minds. . . . Darwinian theory has itself become an orthodoxy preached by its adherents with religious fervor, and doubted, they feel, only by a few muddlers imperfect in scientific faith."

Somewhere between the credibility of the argument that evolution has a prophet and that it is a social creed is the authors' suggestion that professional evolutionists function as a kind of intellectual clergy for Western culture with a "secret-knowledge-known-only-to-a-select-few."

When inconsistencies and problems with naturalistic evolution are raised, they are frequently countered with ridicule, giving the impression that the scientific aspects of the Theory of Naturalistic Evolution are highly complex and can never be understood by ordinary people: not by a physicist like the author and not even by a Nobel laureate such as astrophysicist Sir Fred Hoyle. The terminology sometimes seems deliberately incomprehensible as if to emphasize that the fundamentals of neo-Darwinism can be understood only by a few great men and women of science.

Pierre-Paul Grasse states: "We rarely discover these rules [which govern the living world] because they are highly complex." Probability arguments such as those outlined below, which seem compelling, are often countered with flip comments such as "Biologists don't find that a problem"—as if to cite a higher authority. Fundamental questions, such as the evolution of the eye, are answered with speculation but with scant supporting facts. (One example is the PBS documentary on that topic, which is available in the PBS online library.) Such attitudes are more appropriate to clerics than to scientists; inconsistencies and problems in other branches of science are countered with scientific evidence, not mere rhetoric. Scientists are taught to distrust nebulous calls to higher authority and distracting arguments; as Hoyle once said about the Theory of Naturalistic Evolution: "Be suspicious of a theory if more and more hypotheses are needed to support it as new facts become available, or as new considerations are brought to bear."

Having shown the ways the theory of evolution conforms to the sociological notion of myth, the remainder of the article attempts to illustrate how evolutionary theory falls short by science's own self-imposed strictures. Not being a scientist, and not really caring whether or not evolution is good science, I will leave those arguments for anyone who wants to track down the article. What is striking to me is how compelling the overall thesis of the article is, regardless of the strength of the individual arguments. It is hard to look at evolution and not realize just how thoroughly it functions in our culture much in the same way that creation myths have in all cultures previous. It has become "an article of faith and a test of orthodoxy" from which no one in our society can escape. The myth of naturalistic evolution is a necessary construct, whether factually accurate or not, for justifying the naturalism and materialism that prop up Western notions of politics, science, and ethics.

Many of the parallels Henry and Dyke draw are strained, many will find suspect their assertion that evolution is more myth than science (which is really unnecessary to the claim that evolution functions sociologically as a myth), and it is hard not to be critical on a number of levels of the conclusion that "the existence of a Creator-God has much more evidence than the Theory of Naturalistic Evolution." Yet, these deficiencies notwithstanding, Henry and Dyke make an important contribution to Western self-understanding with this article. "Whether it is right or whether it is wrong," naturalistic evolution has proved a powerful myth--arguably the governing myth--in Western culture. This ought to allow us not only to open evolution to more careful scientific critique, which seems to be the authors' aim, but also to cultural critique. Understanding evolution as myth and embracing the iconoclastic postmodern programme, it is paramount that contemporary society begin to reevaluate evolution as a test for orthodoxy in politics, academia, and culture at large. The time has come to consider again the claims of philosopher of science Wolfgang Smith and to actualize their implications:

The doctrine of evolution has swept the world, not on the strength of its scientific merits, but precisely in its capacity as a Gnostic myth. It affirms, in effect, that living beings created themselves, which is, in essence, a metaphysical claim. . . . evolutionism is in truth a metaphysical doctrine decked out in scientific garb.

Labels:

Daniel J. Dyke,

evolution,

Hugh Henry,

myth,

science,

Wolfgang Smith

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

Science, Adolescence, and Legal Culpability

It is important to begin with the disclaimer that it is not here my intention to discuss moral culpability, particularly given that the focus will be on the possibility of a diminished culpability. I do not in any sense advocate acceptance of diminished moral culpability which would be inconsistent with a belief that morals operate in absolute categories. Moreover, with specific regard to adolescence, I have more or less entirely abandoned the self-serving and unbiblical doctrine of an age of accountability which had been taught me in my youth. As I get older (and hopefully wiser), I increasingly see the value in the historic Christian recognition of sinful impulses even in infancy. This is not, however, the place to argue either the absoluteness of morality or the moral culpability of children. Instead, I want to look at the possibility of a diminished legal culpability.

On this point, the recent Chardon High School shooting has caught my attention and specifically the recent indications that T. J. Lane will be tried as an adult. The legitimacy of trying minors as adults is, admittedly, difficult to navigate. The arbitrary nature with which American children are unceremoniously ushered into adulthood functions both to retard legitimate maturation in those still technically minors (consider the contentious age of consent laws) and to foist tremendous responsibility onto an unprepared, uninformed section of the populace (consider the rapidity with which teenagers are allowed to legally accrue massive student loan debt). There seems to be legitimate cultural argument both for treating the crimes of minors as intrinsically different and for occasionally ignoring that distinction when appropriate. The question is, and ought to be, how to distinguish between times when it is appropriate to recognize the unique legal status of minors and when it is necessary to ignore it. The state of Colorado offers three primary criteria for consideration:

At first glance, this seems like a relatively reasonable, objective rubric for determining the level of legal culpability for minors. Yet I wonder if perhaps the science which underlies our distinct treatment of minors might not reveal that one of these categories is substantially weaker than the others. It is important to realize that the argument for a diminished legal capacity is not merely cultural but neurological. Studies on teenagers having shown that "impulse control, planning and decisionmaking are largely frontal cortex functions that are still maturing during adolescence...In sum, a large and compelling body of scientific research on the neurological development of teens confirms a long-held, common sense view: teenagers are not the same as adults in a variety of key areas such as the ability to make sound judgments when confronted by complex situations, the capacity to control impulses, and the ability to plan effectively. Such limitations reflect, in part, the fact that key areas of the adolescent brain, especially the prefrontal cortex that controls many higher order skills, are not fully mature until the third decade of life. Teens are full of promise, often energetic and caring, capable of making many contributions to their communities, and able to make remarkable spurts in intellectual development and learning. But neurologically, they are not adults."

With this in mind, it is easy to see why the age of the offender is a legitimate concern for determining legal culpability. After all, physical maturation is directly correlated to the ability of the brain to delay gratification. In lacking a fully functional ability to control impulses, positive and negative, adolescents cannot be held responsible for their actions at an equal level with adults who presumably have the ability to resist criminal urges. Certainly the case can be made that age is an inadequate indicator of physical and psychological development (hence the flaw in age of consent laws), but in the absence of a pragmatic alternative it makes sense to employ age as an important category. There is even logic to including the offender's previous criminal record, insofar as previous encounters with the judicial system ought to have acted as a catalyst for forming connections between criminal behavior and its consequences. Whatever may be said about the development of the frontal cortex in adolescents, even a dog can learn not to chew on your shoes after having been smacked with a rolled up newspaper a requisite number of times.

The connection between the severity of the crime and legal culpability seems less substantial. The scientific basis for trying minors as minors rests on what is tantamount to a mental defect on the part of teenagers. The adolescent mind lacks the necessary maturity--in an anatomical not a cultural sense--to entirely grasp the severity and repercussions of its actions in the moment. If not completely impotent, adolescents are at least severely disabled as they attempt to govern their baser impulses, maps out the consequences of their actions, and sympathize with a reality beyond their limited scope of contact and power. In other words, it is the very fact that a fourteen year old can shoot someone almost as easily as he or she could pat someone on the back which requires minors to be treated differently by the legal system. Given this psycho-physiological handicap, how can we include the severity of the crime in the calculation? It is the inability to conceive adequately of severity that constitutes the essence of the adolescent problem.

Which brings us full circle back to T. J. Lane. Admittedly, at seventeen, he is approaching the legal threshold for adulthood, and his ability to grasp the consequences of his actions in the moment may have been more developed than not. Certainly there is some question as to his background which may come to light as the judge debates whether or not to release his county social services record. Still, I cannot help but wonder if the push to have Lane tried as an adult has less to do with a reasoned philosophy of legal culpability and more to do with the blood lust of the community on behalf of the victims. After all, it is hardly overly cynical to suggest that Lane's crime warrants national attention and judicial rigor not because three people died but because they died in a white, suburban high school. (Based on CDC numbers, an average of eighty-four nameless, faceless people die every day in America from violence involving guns--some legal, most not.) Aside from race and affluence, what makes these deaths so heinous is that they were children, in a state of presumed innocence, whose lives did not deserve to be cut short when they had so much growing and developing left to do. I submit, that T. J. Lane, no less a child than his victims, deserves the same consideration.

On this point, the recent Chardon High School shooting has caught my attention and specifically the recent indications that T. J. Lane will be tried as an adult. The legitimacy of trying minors as adults is, admittedly, difficult to navigate. The arbitrary nature with which American children are unceremoniously ushered into adulthood functions both to retard legitimate maturation in those still technically minors (consider the contentious age of consent laws) and to foist tremendous responsibility onto an unprepared, uninformed section of the populace (consider the rapidity with which teenagers are allowed to legally accrue massive student loan debt). There seems to be legitimate cultural argument both for treating the crimes of minors as intrinsically different and for occasionally ignoring that distinction when appropriate. The question is, and ought to be, how to distinguish between times when it is appropriate to recognize the unique legal status of minors and when it is necessary to ignore it. The state of Colorado offers three primary criteria for consideration:

- The age of the offender.

- The offender's previously criminal record.

- The severity of the crime.

At first glance, this seems like a relatively reasonable, objective rubric for determining the level of legal culpability for minors. Yet I wonder if perhaps the science which underlies our distinct treatment of minors might not reveal that one of these categories is substantially weaker than the others. It is important to realize that the argument for a diminished legal capacity is not merely cultural but neurological. Studies on teenagers having shown that "impulse control, planning and decisionmaking are largely frontal cortex functions that are still maturing during adolescence...In sum, a large and compelling body of scientific research on the neurological development of teens confirms a long-held, common sense view: teenagers are not the same as adults in a variety of key areas such as the ability to make sound judgments when confronted by complex situations, the capacity to control impulses, and the ability to plan effectively. Such limitations reflect, in part, the fact that key areas of the adolescent brain, especially the prefrontal cortex that controls many higher order skills, are not fully mature until the third decade of life. Teens are full of promise, often energetic and caring, capable of making many contributions to their communities, and able to make remarkable spurts in intellectual development and learning. But neurologically, they are not adults."

With this in mind, it is easy to see why the age of the offender is a legitimate concern for determining legal culpability. After all, physical maturation is directly correlated to the ability of the brain to delay gratification. In lacking a fully functional ability to control impulses, positive and negative, adolescents cannot be held responsible for their actions at an equal level with adults who presumably have the ability to resist criminal urges. Certainly the case can be made that age is an inadequate indicator of physical and psychological development (hence the flaw in age of consent laws), but in the absence of a pragmatic alternative it makes sense to employ age as an important category. There is even logic to including the offender's previous criminal record, insofar as previous encounters with the judicial system ought to have acted as a catalyst for forming connections between criminal behavior and its consequences. Whatever may be said about the development of the frontal cortex in adolescents, even a dog can learn not to chew on your shoes after having been smacked with a rolled up newspaper a requisite number of times.

The connection between the severity of the crime and legal culpability seems less substantial. The scientific basis for trying minors as minors rests on what is tantamount to a mental defect on the part of teenagers. The adolescent mind lacks the necessary maturity--in an anatomical not a cultural sense--to entirely grasp the severity and repercussions of its actions in the moment. If not completely impotent, adolescents are at least severely disabled as they attempt to govern their baser impulses, maps out the consequences of their actions, and sympathize with a reality beyond their limited scope of contact and power. In other words, it is the very fact that a fourteen year old can shoot someone almost as easily as he or she could pat someone on the back which requires minors to be treated differently by the legal system. Given this psycho-physiological handicap, how can we include the severity of the crime in the calculation? It is the inability to conceive adequately of severity that constitutes the essence of the adolescent problem.

Which brings us full circle back to T. J. Lane. Admittedly, at seventeen, he is approaching the legal threshold for adulthood, and his ability to grasp the consequences of his actions in the moment may have been more developed than not. Certainly there is some question as to his background which may come to light as the judge debates whether or not to release his county social services record. Still, I cannot help but wonder if the push to have Lane tried as an adult has less to do with a reasoned philosophy of legal culpability and more to do with the blood lust of the community on behalf of the victims. After all, it is hardly overly cynical to suggest that Lane's crime warrants national attention and judicial rigor not because three people died but because they died in a white, suburban high school. (Based on CDC numbers, an average of eighty-four nameless, faceless people die every day in America from violence involving guns--some legal, most not.) Aside from race and affluence, what makes these deaths so heinous is that they were children, in a state of presumed innocence, whose lives did not deserve to be cut short when they had so much growing and developing left to do. I submit, that T. J. Lane, no less a child than his victims, deserves the same consideration.

Labels:

Chardon High School,

culpability,

law,

news,

science,

T. J. Lane,

violence

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Leading Atheist on What's Wrong with Atheism

Prominent atheist Alain de Botton recently gave an interview to Talking Philosophy regarding his latest book, Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer's Guide to the Uses of Religion. The purpose of the book is to look at how religion has functioned for society and, insofar as religion has been successful in its more beneficent efforts, to identify areas in which a purely secular culture may profit from the adoption and adaptation of religious ideas and methods. In fairness then, my admittedly sensationalist title might better read "Leading Atheist on What's Right with Religion." One of the features of the interview, however, that makes it immediately inviting for believers to read is that de Botton is upfront and candid about what he sees as four potential dangers that atheism faces and to which theism is not (or at least less) susceptible. It is critical to note that de Botton rightly sees these as pitfalls to be avoided rather than inescapable defects in atheism. Below are his four dangers of a purely secular worldview, with my own elaboration of each included.

Of course, none of this commends theism any more than it condemns atheism. It certainly wasn't my purpose to try to do either, nor was it de Botton's. It does, however, represent a necessary exercise for atheists who want to have a rigorous understanding of their own worldview. The impulse among so many New Atheists is to expend all of their available energy finding every conceivable flaw in theism. It is fruitful, therefore, to see de Botton critique this emphasis latter in the interview:

What de Botton ultimately recommends to his atheist readers is a middle path between belief and militant unbelief. It is a perhaps a more genuinely reasonable path that is not ashamed to disbelieve but that at the same time recognizes the real role that belief has played in society. It recognizes the importance of religion has played in addressing central human questions that are not done away with simply because religions are done away with. It applauds the good, abhors the bad, and, at the end of the day, finishes in a more satisfied and stronger position than the New Atheists.

- Individualism: When the absolute and transcendent "other" in God is removed from the equation, humanity becomes a level-playing field. More destructively, as the only human who is me, I am faced with the overwhelming temptation to understand and interact with the world as if I am somehow special within it, to behave as if my will is intrinsically more valuable (because it, tautologically, coincides perfectly with what I want). One feature which finds near ubiquitous emphasis in the world's religions, as universalists are quick to point out, is some version of the ethical imperative "Treat one another as you would like to be treated." In a world without religion, such an ethos need not necessarily exist.

- Technological Perfectionism: Even among the religious, there seems to be a pervasive belief that technology is marching inevitably toward social utopia. It plays out in every corner of our society. With enough research, we will do away with cancer and heart disease and AIDS. It never occurs to us that there may be new incurable diseases just around the corner. With enough research, green energy will replace oil and give us peace in the Middle East. It never occurs to us that we were making war before we were making cars. Accurately, de Botton critiques the prevailing myth that "it is just a matter of time before scientists have cured us of the human condition." In a world where science is the ultimate arbiter of truth, there is a temptation to create a techno-soteriology that is unrealistic and, to a degree, dangerous.

- Contemporary Exceptionalism: A world without God is more prone to lack not only a sacred history but also a normative image of the future and an eschatological vision of an ultimate telos. The result is the mistaken belief that the now is somehow privileged because we live in it. There is a tendency to want to downplay the achievements and importance of past humans who lived in past moments and to ignore the possible achievements and importance of future humans who will live in moments that we will never experience. By virtue of our presence in this place and moment, there is tendency to lose sight of just how transient our time is and how qualified the importance of our achievements is.

- Ethical Nihilism: This is not to suggest that one cannot be an atheist and be ethical. I have atheist acquaintances who are at times genuinely upset that I won't embrace the common evangelical tactic of claiming that there are no morals without God. It is impossible to deny, however, that there are internally consistent ethical systems which are entirely atheistic. The fear here is not whether or not someone can be ethical without God but what it is that compels them to be ethical without God. Evil, such as it is, becomes blurred in a system where humans are left to identify it independently. As we struggle to decide what is right and what is wrong, there is not ultimate, incontestable arbiter of whose definition of evil is correct. There is nothing to compel me to accept your ethos, nothing to make you accept mine. Rampant ethical relativism, unchecked, quickly resolves itself into a society incapable of mustering the kind of moral majority necessary to resist corruption by evil. Ethics is possible for atheists, but the issue certainly becomes cloudier with the removal of God.

Of course, none of this commends theism any more than it condemns atheism. It certainly wasn't my purpose to try to do either, nor was it de Botton's. It does, however, represent a necessary exercise for atheists who want to have a rigorous understanding of their own worldview. The impulse among so many New Atheists is to expend all of their available energy finding every conceivable flaw in theism. It is fruitful, therefore, to see de Botton critique this emphasis latter in the interview:

What is your view of the so-called New Atheist critique advanced by Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens and others?

Attempting to prove the non-existence of god can be entertaining...Though this exercise has its satisfactions, the real issue is not whether god exists or not, but where one takes the argument to once one decides that he evidently doesn’t. The premise of my book is that it must be possible to remain a committed atheist and nevertheless to find religions sporadically useful, interesting and consoling – and be curious as to the possibilities of importing certain of their ideas and practices into the secular realm.

What de Botton ultimately recommends to his atheist readers is a middle path between belief and militant unbelief. It is a perhaps a more genuinely reasonable path that is not ashamed to disbelieve but that at the same time recognizes the real role that belief has played in society. It recognizes the importance of religion has played in addressing central human questions that are not done away with simply because religions are done away with. It applauds the good, abhors the bad, and, at the end of the day, finishes in a more satisfied and stronger position than the New Atheists.

Labels:

Alain de Botton,

atheism,

individualism,

nihilism,

science

Saturday, January 28, 2012

Conservatives, Racists, and Journalists Are Idiots

Sensationalist titles are a journalistic standby, and my years as an editor on my high school paper taught me that they can be used liberally, provided the sensationalism goes no further than the title. So, when I saw an article in a news feed entitled "Low IQ & Conservative Beliefs Linked to Prejudice," I expected to find the impression given in the admittedly engaging title quickly qualified. It's obvious, of course, what the catchy headline is trying to insinuate: conservatives are racists and idiots. After all, the actual phrasing--which indicates that racists are idiots and conservatives--is not nearly as interesting. Clearly the purpose is to draw in conservatives who are indignant at the idea that they could be branded idiots and racists and draw in liberals who are hoping that their deepest held beliefs about conservatives will be vindicated. The truth, of course, which we should all know from the outset is that conservatives and liberals are both idiots (a fact reenforced in the very act of buying into the title and clicking on the article).

To my disappointment (and, I admit, shock) the article gives every appearance of holding to the sensational idea, however, that there is a substantial and meaningful correlation between having a low IQ and being a conservative, being a racist and being a conservative. The writers hit you with gems like "Low-intelligence adults tend to gravitate toward socially conservative ideologies, the study found" and "Polling data and social and political science research do show that prejudice is more common in those who hold right-wing ideals that those of other political persuasions." The article is more than halfway finished before the writers throw poor, dumb conservatives a bone:

Even here, however, it is clear that the intelligent conservative is like a tall woman (an example the article actually uses), the exception not the rule. And so the writers plug euphemistically on, insisting, "Nonetheless, there is reason to believe that strict right-wing ideology might appeal to those who have trouble grasping the complexity of the world." Only in their final thoughts, do the writers think to mention that the study results show a correlative rather than causative connection between the three variables. A professor at the University of Virginia, who was in no way involved in the study, is brought in to play devil's advocate and present a more reasoned analysis of the data:

Go figure. There may be a chance, however slight, that in actuality extreme political ideologies of all forms attract their own special kinds of idiots. Why not lead with that wonderful tidbit, or even just a token teaser that there are some who interpret the findings differently? It is just the tried-and-true liberal media bias, famed in song and story and Republican debate rant? Is it just bad journalism, an unfortunate ignorance on the part of the writer about how the article will be perceived? I don't pretend to know. I also don't know whether or not the average reader of either political persuasion will be clever enough to see from the start how slanted the presentation of the study is, though I would hope so. What I do know, or at least suspect, is that is a correlation between low IQ and believing that dumb people are primarily the residents of one political faction.

To my disappointment (and, I admit, shock) the article gives every appearance of holding to the sensational idea, however, that there is a substantial and meaningful correlation between having a low IQ and being a conservative, being a racist and being a conservative. The writers hit you with gems like "Low-intelligence adults tend to gravitate toward socially conservative ideologies, the study found" and "Polling data and social and political science research do show that prejudice is more common in those who hold right-wing ideals that those of other political persuasions." The article is more than halfway finished before the writers throw poor, dumb conservatives a bone:

Hodson was quick to note that the despite the link found between low intelligence and social conservatism, the researchers aren't implying that all liberals are brilliant and all conservatives stupid. The research is a study of averages over large groups, he said.

"There are multiple examples of very bright conservatives and not-so-bright liberals, and many examples of very principled conservatives and very intolerant liberals," Hodson said.

Even here, however, it is clear that the intelligent conservative is like a tall woman (an example the article actually uses), the exception not the rule. And so the writers plug euphemistically on, insisting, "Nonetheless, there is reason to believe that strict right-wing ideology might appeal to those who have trouble grasping the complexity of the world." Only in their final thoughts, do the writers think to mention that the study results show a correlative rather than causative connection between the three variables. A professor at the University of Virginia, who was in no way involved in the study, is brought in to play devil's advocate and present a more reasoned analysis of the data:

The researchers controlled for factors such as education and socioeconomic status, making their case stronger, Nosek said. But there are other possible explanations that fit the data. For example, Nosek said, a study of left-wing liberals with stereotypically naïve views like "every kid is a genius in his or her own way," might find that people who hold these attitudes are also less bright. In other words, it might not be a particular ideology that is linked to stupidity, but extremist views in general.

"My speculation is that it's not as simple as their model presents it," Nosek said. "I think that lower cognitive capacity can lead to multiple simple ways to represent the world, and one of those can be embodied in a right-wing ideology where 'People I don't know are threats' and 'The world is a dangerous place'. ... Another simple way would be to just assume everybody is wonderful."

Go figure. There may be a chance, however slight, that in actuality extreme political ideologies of all forms attract their own special kinds of idiots. Why not lead with that wonderful tidbit, or even just a token teaser that there are some who interpret the findings differently? It is just the tried-and-true liberal media bias, famed in song and story and Republican debate rant? Is it just bad journalism, an unfortunate ignorance on the part of the writer about how the article will be perceived? I don't pretend to know. I also don't know whether or not the average reader of either political persuasion will be clever enough to see from the start how slanted the presentation of the study is, though I would hope so. What I do know, or at least suspect, is that is a correlation between low IQ and believing that dumb people are primarily the residents of one political faction.

Labels:

conservatism,

intelligence,

journalism,

news,

politics,

racism,

science

Saturday, August 13, 2011

The Absurd and Science

Perhaps the most beautiful and compelling of all the passages I have encountered in Camus is his critique of the insufficiency of science to resolve the problem of the absurd. It is the ultimate aim of secluarist scientists to reduce the world to a mathematical series of formulas, and they assume that such a reduction is more or less inevitable. They treat the comprehensibility of the world and their materialist philosophy as so self-evident as to defy criticism. Camus, and of course others, have rightly observed that by all objective standards, science always ultimately dissolves not into scientific formulas but into romantic verse:

It is intriguing how Camus' despair at the inability of science to resolve the absurd is also vividly poetic. It mirrors the sentiments of Petru Dumitriu as he laments the simultaneously mathematical and incomprehensible universe. But while Camus stops with the lament that he cannot find assurance that the world is his, Dumitriu so embraces the foreignness of the world that, so far from being his, he insists that it must belong to someone else:

The most perfect parallel to Camus' critique of science (at least that I have found) is actually in the work of G. K. Chesterton. Writing well before the birth of absurdism, Chesterton anticipated Camus' observations about science and its inability to adequately give answers to the truly pressing questions of the world. Just as it completely failed to resolve the problem of the absurd, science was totally impotent in the face of the ultimate question: why?

Chesterton goes on with astonishing parallels to Camus and his complaint that science inevitably collapses into poetry:

Just as with Camus, Chesterton himself slips easily into his own rhetorical poetry when speaking about the world. They admit that awed ignorance is the appropriate response to reality and recognize that even science (in its own cold, self-deluded way) will always end at the same place as everyone else: wide-eyed wonder. It certainly raises questions about the whether or not apophatic thinkers have had it right all along; the end of human knowledge is silence before God. More to the point though, this realization should work to resolve the lingering fear that has been created by the false triumphalism of science with reference to religion. Faith has nothing to fear in science because science ultimately has nothing to say to faith. It is itself just a gelid, mechanical mysticism which has had the unfortunate fate of being so convinced by its own facade that it thinks it is somehow above and apart. In truth, science offers only transient answers to transient problems. It crumbles in the face of the absurd, like all human effort.

And here are the trees and I know their gnarled surface, water and I feel its taste. These scents of grass and stars at night, certain evenings when the heart relaxes -how shall I negate this world whose power and strength I feel? Yet all the knowledge on earth will give me nothing to assure me that this world is mine. You describe it to me and you teach me to classify it. You enumerate its laws and in my thirst for knowledge I admit that they are true. You take apart its mechanisms and my hope increases. At the final stage you teach me that this wondrous and multicolored universe can be reduced to the atom and that the atom itself can be reduced to the electron. All this is good and I wait for you to continue. But you tell me of an invisible planetary system in which electrons gravitate around a nucleus. You explain this world to me with an image. I realize then that you have been reduced to poetry: I shall never know. Have I the time to become indignant? You have already changed theories. So that science that was to teach me everything ends up in a hypothesis, that lucidity founders in metaphor, that uncertainty is resolved in a work of art. What need had I of so many efforts? The soft lines of these hills and the hand of evening on this troubled heart teach me much more. I have returned to my beginning. I realize that if through science I can seize phenomena and enumerate them, I cannot, for all that, apprehend the world. Were I to trace its entire relief with my finger, I should not know any more. And you give me the choice between a description that is sure but that teaches me nothing and hypotheses that claim to teach me but that are not sure. A stranger to myself and to the world, armed solely with a thought that negates itself as soon as it asserts, what is this condition in which I can have peace only by refusing to know and to live, in which the appetite for conquest bumps into walls that defy its assaults? To will is to stir up paradoxes. Everything is ordered in such a way as to bring into being that poisoned peace produced by thoughtlessness, lack of heart, or fatal renunciations.

It is intriguing how Camus' despair at the inability of science to resolve the absurd is also vividly poetic. It mirrors the sentiments of Petru Dumitriu as he laments the simultaneously mathematical and incomprehensible universe. But while Camus stops with the lament that he cannot find assurance that the world is his, Dumitriu so embraces the foreignness of the world that, so far from being his, he insists that it must belong to someone else:

For nothing is simple, and the universe is mathematicable, but incomprehensible -- really incomprehensible, and really constructed according to a plan that is not a human one.

The most perfect parallel to Camus' critique of science (at least that I have found) is actually in the work of G. K. Chesterton. Writing well before the birth of absurdism, Chesterton anticipated Camus' observations about science and its inability to adequately give answers to the truly pressing questions of the world. Just as it completely failed to resolve the problem of the absurd, science was totally impotent in the face of the ultimate question: why?

In fairyland we avoid the word "law"; but in the land of science they are singularly fond of it. Thus they will call some interesting conjecture about how forgotten folks pronounced the alphabet, Grimm's Law. But Grimm's Law is far less intellectual than Grimm's Fairy Tales. The tales are, at any rate, certainly tales; while the law is not a law. A law implies that we know the nature of the generalisation and enactment; not merely that we have noticed some of the effects. If there is a law that pick-pockets shall go to prison, it implies that there is an imaginable mental connection between the idea of prison and the idea of picking pockets. And we know what the idea is. We can say why we take liberty from a man who takes liberties. But we cannot say why an egg can turn into a chicken any more than we can say why a bear could turn into a fairy prince. As IDEAS, the egg and the chicken are further off from each other than the bear and the prince; for no egg in itself suggests a chicken, whereas some princes do suggest bears...It is the man who talks about "a law" that he has never seen who is the mystic.

Chesterton goes on with astonishing parallels to Camus and his complaint that science inevitably collapses into poetry: